By Megan Widdows

Bacteria are often thought of as a damaging and dangerous. This is understandable – bacteria are the cause of countless deadly diseases. Despite antibiotics being developed in the 1940s, bacterial infections still affect millions of people every year, making countless people sick and even proving deadly for many.

But in actual fact, whilst some bacteria are indeed harmful, others are actually needed to keep us healthy. These helpful bacteria are known as commensals. Commensal bacteria make up a large proportion our microbiome, which is a collection of helpful microorganisms that play important roles in maintaining our health. Commensal bacteria can be found all over your body including all over your skin, lining your airways and in your digestive system.

Your microbiome is essential to your health, influencing your digestion, regulating your immune system, helping to produce several key vitamins and providing protection against harmful bacteria. The role of the microbiome is still being studied, but it is thought to be important for dozens of other bodily functions too. Increasingly, problems with the microbiome, known as dysbiosis, are being linked to a number of diseases including obesity and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes.

The main role of your immune system is to spot potentially dangerous bacteria and other pathogens and eliminate them. So how does the microbiome avoid detection and destruction by the host immune system?

Until recently, no one knew the answer to this question. A recent scientific study aimed to find out.

The study focussed on innate immunity, one of two arms of an immune response. The innate immune system provides the first line of defence against a pathogen by producing a non-specific, fast acting response to any invasion. It consists of physical barriers such as your skin, tears and stomach acid combined with white blood cells that seek out and destroy non-self cells. By contrast, the adaptive immune system is highly specific to each type of pathogen, but it takes around a week to be fully effective. It produces unique antibodies that bind to a pathogen and trigger its elimination.

The innate immune system is activated by detecting special molecular patterns that are common across many species of bacteria. These include the proteins that make up the bacterial flagella (tail-like structures involved in cell movement) and receptors that stick out from the surface of the bacteria.

However, since these molecular patterns are common across many different species of bacteria, it is likely that they will also be present in the commensal bacteria that make up your microbiome. This means commensal bacteria would also trigger an innate immune response, despite being beneficial to your health. This could cause many problems including the destruction of your essential microbiome and the continuous activation of your immune system, both of which would come at a great cost to your health and chance of survival.

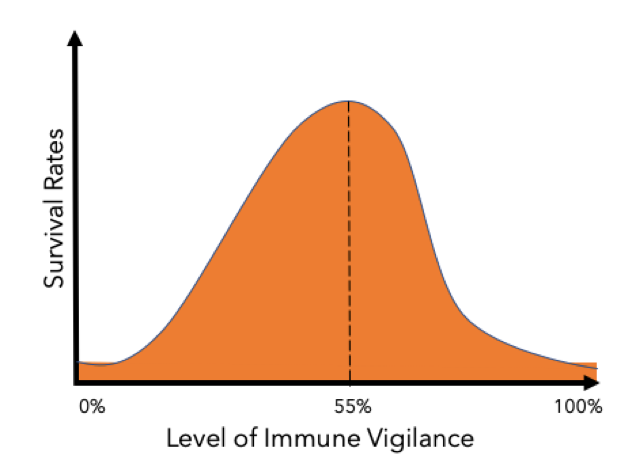

As a result, your immune system needs to find a way maintaining a diverse microbiome while still defending itself against pathogens with similar molecular features. It achieves this by altering its levels of immune vigilance, or the level of innate immune activity. Scientists compared how different proportions of pathogenic and commensal bacteria affected the likelihood of the host surviving using mathematical modelling.

They found that with very high levels of immune vigilance (~100%), pathogenic bacteria are almost always removed, preventing infection. However, this comes at a high cost. The microbiome is also completely eliminated, creating major health problems and drastically reducing the host’s chance of survival. Even if the host survives, the elevated immune response requires lots of energy, reducing the host’s growth and reproductive success and triggering internal inflammation in the body. Long term inflammation has also been linked to increased risk of heart disease, autoimmune diseases, cancer and obesity.

With very low levels of immune vigilance, there are none of the associated problems of immunity and no removal of the microbiome. However, with no immune response, the host survival rate is reduced even further due to the high mortality of an unchecked infection. This too is not a favourable outcome.

The outcome of the scientists mathematical modelling was that there is an ideal middle ground of around 55% immune vigilance. At this level, there are relatively low costs associated with immunity and only small amounts of microbiome destruction, as well as low chances of mortality from pathogens.

The scientists determined that by modulating immune vigilance in this way, the host’s immune system “distinguishes” between pathogenic and commensal bacteria, creating the much desired balance between preventing infection and conserving the microbiome.

The study mentioned in this article can be found here. A glossary of key terms is provided below.

Tell us what you think about this blog…

We are trying to understand who reads our blogs and why, to help us improve their content.

By completing this survey, you agree that you are over the age of 18 and that your responses can be used in research at the University of Sheffield to evaluate the effect of blogging in science communication.

Glossary

Adaptive immune system – a sub-system of the immune system that is made of specialised cells and processes that develop in response to a pathogen. The specific response results in the targeted destruction of a pathogen. Some of these cells are memory cells that remain in the bloodstream, and quickly eliminate the pathogen in the case of reinfection.

Commensal bacteria – bacteria that derive food or other benefits from others, or their host, without causing harm

Dysbiosis – an imbalance in the types of microorganisms present in the microbiome of an individual which is thought to contribute to a range of health conditions

Immune vigilance – the process used by the immune system to detect and destroy pathogens

Innate immune system – the non-specific defence mechanisms that form the first line of defence against pathogens