A new study published in Evolution Letters has shown that the formation of new species does not necessarily require complete genomic isolation. Author Prof. Markus Pfenninger tells us more about the findings.

How we think about species, speciation and hybridisation is not only of academic interest, but also influences society and politics. Biological justifications for racism and the rejection of intermingling are essentially based on the seeming rarity of pairings between species and the allegedly negative consequences for their offspring.

We now know that hybridizations are more the rule than the exception in the animal kingdom and that speciation can also take place with continued genetic exchange. The prevailing theory suggested that regular gene flow through successful pairings between populations is the main barrier to their segregation into species. In recent years, however, theoretical and empirical work has shown that speciation is possible under certain circumstances despite gene flow. It is not clear how widespread this phenomenon of speciation with gene flow is and how the speciation processes take place over time. In particular, it is unknown whether divergence processes once begun will always and inevitably lead to complete genomic and reproductive isolation sooner or later. If they do, this would mean that the diverging populations eventually become “real” species in the sense of the widely recognized biological species concept.

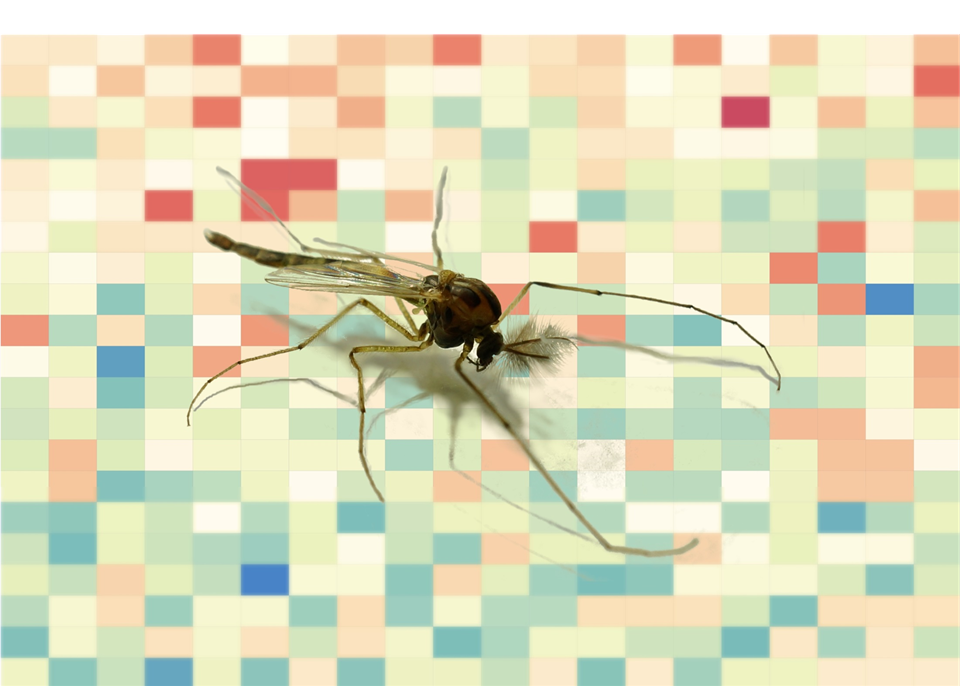

In our recently published comparison of the genomes of individuals of two regularly hybridizing sister species of mosquitoes (Chironomus riparius and C. piger), we show that these species formed within a short period, millions of generations ago. The two species occur in a spatial mix with one another throughout the northern hemisphere, but prefer ecologically different habitats.

A male Chironomus riparius sitting on a graphical representation of its genome. Photo: Markus Pfenninger.

The speciation process between the two species apparently stopped completely at some point, even before the entire genome was mutually isolated. Hybridization has occurred regularly since then, i.e. they can and continue to mate. The two species regularly exchange a good 70% of their genome, which contains around half of all genes. The taxa remain ecologically recognisable, although they only have 30% of the genome (albeit with the other half of the genes) exclusively for themselves. These isolated areas are quite small and scattered across the genome.

Half of the genes that are not exchanged are therefore apparently responsible for keeping the species different. Apart from genes that are related to the known ecological differences between the species (e.g. sensitivity to nitrogen compounds such as nitrite from manure), these are very often genes that have to work closely with other genes at the molecular level. Such genes can be found, for example, in the respiratory chain, protein production or in gates through membranes. At these points, incompatibilities between the different species would obviously be too disturbing.

Our results were able to show that the formation of species does not necessarily have to end in their complete isolation. Rather, there are stable intermediate stages in which related, well-characterized species can gain and maintain their diversity and still share most of their genome with one another. This changes our view of what we call biological species.

Prof. Markus Pfenninger is Head of the Molecular Laboratory in the Department of Molecular Ecology, Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre. The original study is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.