Domesticated animals share similar features, such as floppy ears, curly tails, and smaller brains. A new study published in Evolution Letters challenges the most popular explanation for how these features arose. Lead author Dr Laura Wilson tells us more.

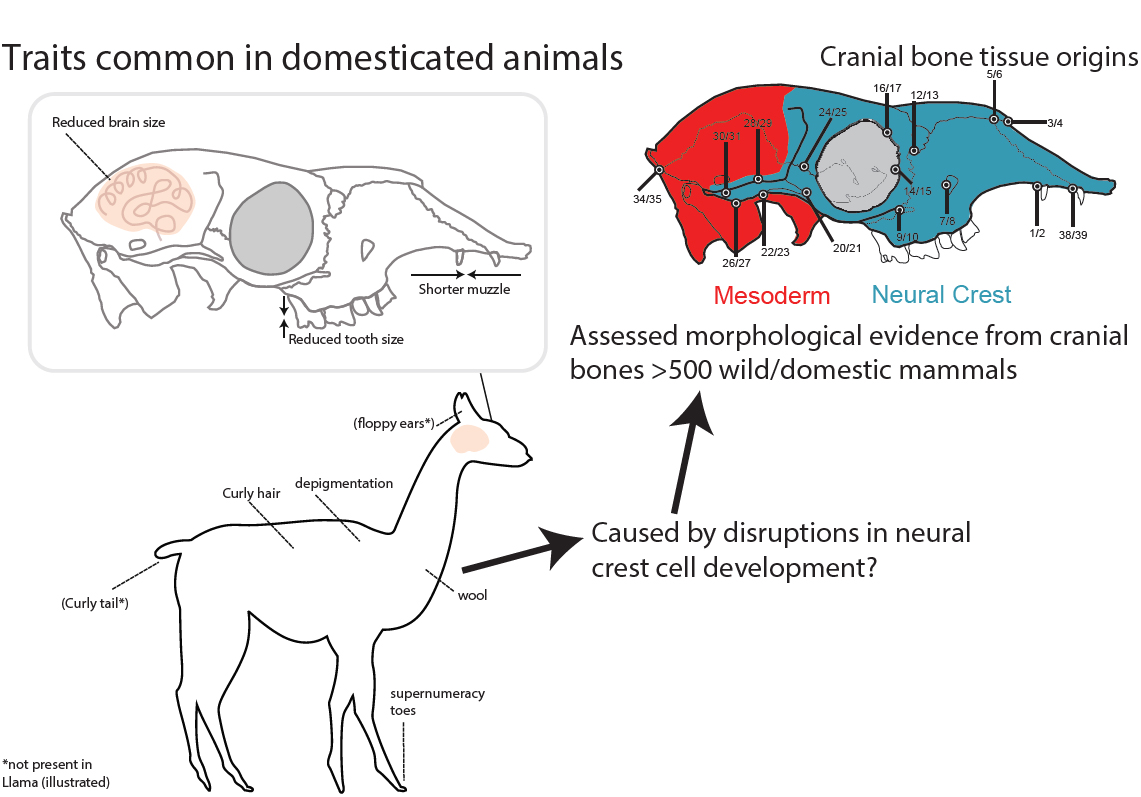

Charles Darwin was first to notice that different domestic animals share similar characteristics despite not being closely related. These features (see Figure 1), called the domestication syndrome, have long puzzled evolutionary biologists – what causes them to develop and how?

In 2014, geneticists proposed a compelling explanation: selection on tameness during the early phases of domestication has led to disruptions in the development of neural crest cells, thereby causing the domestication syndrome. Many tissues in the body – such as cartilage, bone, and connective tissue – form from neural crest cells, and this hypothesis gained much traction in the literature, with supporting evidence surfacing from genomic data.

In our study, we set out to provide the morphological piece of the puzzle, asking whether there was evidence for the neural crest hypothesis among different pairs of wild and domestic mammals.

We used advanced 3D quantitative approaches to record variation in the shape of cranial bones, contrasting those bones of the cranium that form from neural crest (the facial region) with those that derive from mesoderm origins (the vault region) (Figure 1). We compared six pairs of domesticated mammals with their wild relatives using over 500 specimens from historical collections worldwide, including pigs and boars, dogs and wolves, goats and bezoar, llama (Figure 2) and guanaco, among others. These represent examples for each of the different pathways that human-animal interactions have taken (e.g. companionship, provision of food).

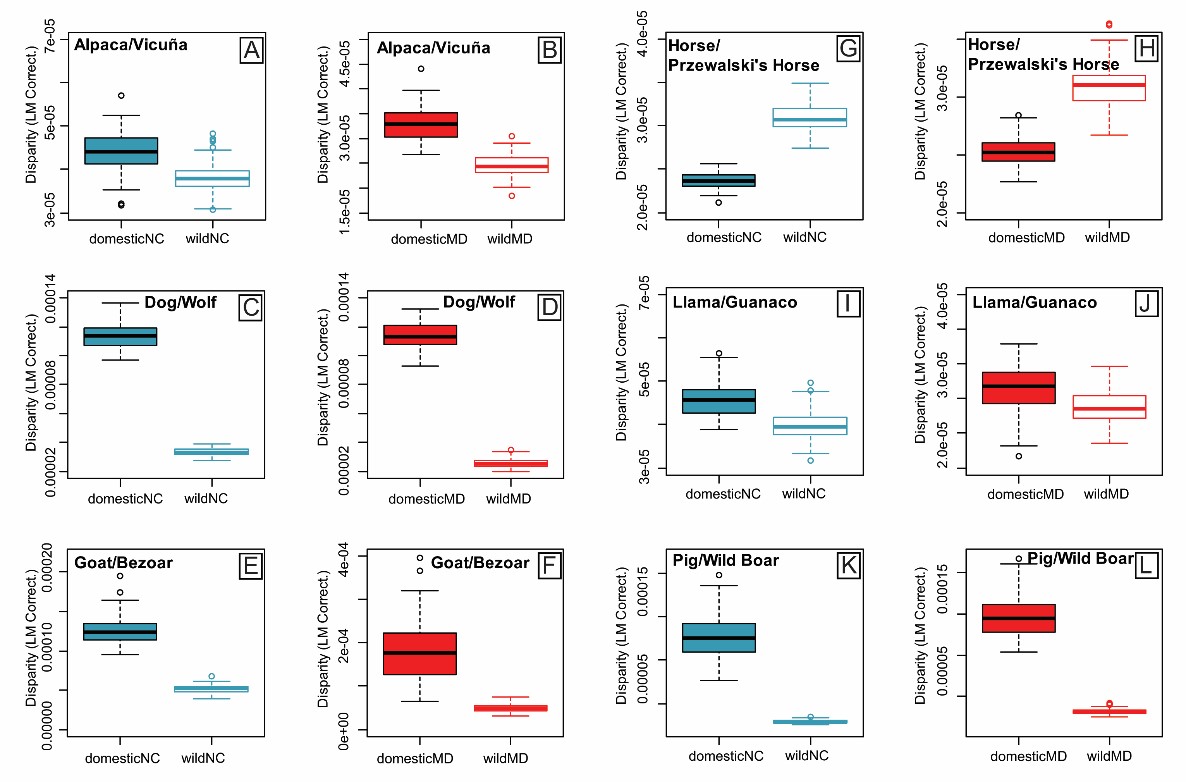

We hypothesized that, if the neural crest hypothesis was responsible for changes associated with domestication, in domestic forms we would recover 1) differences in trait interactions among neural crest bones compared to mesoderm bones and 2) greater variation in shape among neural crest bones.

By adopting the analytical frameworks of modularity and integration, we conducted a suite of morphological-based tests of shape variation. We did not find strong evidence for our predictions under the neural crest hypothesis. Instead, we showed that domestic forms had greater shape variation in both mesoderm and neural crest bones compared to their wild counterparts (Figure 3), and that neural crest bones differed in integration magnitudes (a measure of connectedness) compared to mesoderm bones, but again this was not exclusive to domestic forms.

From the perspective of cranial trait interactions, our results suggesting that the domestication process has co-opted underlying relationships and that the astounding amount of cranial variation that has been generated (e.g. pugs, poodles, great danes) does not appear exclusive to neural crest derived bones.

The validity of the domestication syndrome, and the conditions under which its expectations are met, continue to be a subject of controversy. Our results add to the narrative that domestication is not a ‘one size fits all’ process.

Dr Laura Wilson is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow and Head of Biological Anthropology at the Australian National University.