A new study published in Evolution Letters uses an experimental evolution approach to provide important new insights into how sexual interactions are modulated. Author Dr Francisco Garcia-Gonzalez tells us more.

During the times of Justinian the Great, around the year 550 A.D., the legend says that a ruler in a vast region of what was known as Hispania established a harsh decree affecting the cities contained in his realm: in some cities monogamy was imposed and marriages were to be arranged and enforced to take place between individuals who did not have the chance to select their partner. In the remaining cities, polygamy was allowed in such a way that men and women could choose their partners freely and could reproduce with different partners. In these polygamous populations competition among men for access to females and female mate choice was fierce. The ruler further dictated that half of the cities in each of the two groups were to be subdivided into different sections, while the other half were to remain undivided. Thus, there were four different groups of populations: undivided monogamous, divided monogamous, undivided polygamous and divided polygamous. The final rule stated that the decree had to be in place for over a thousand years.

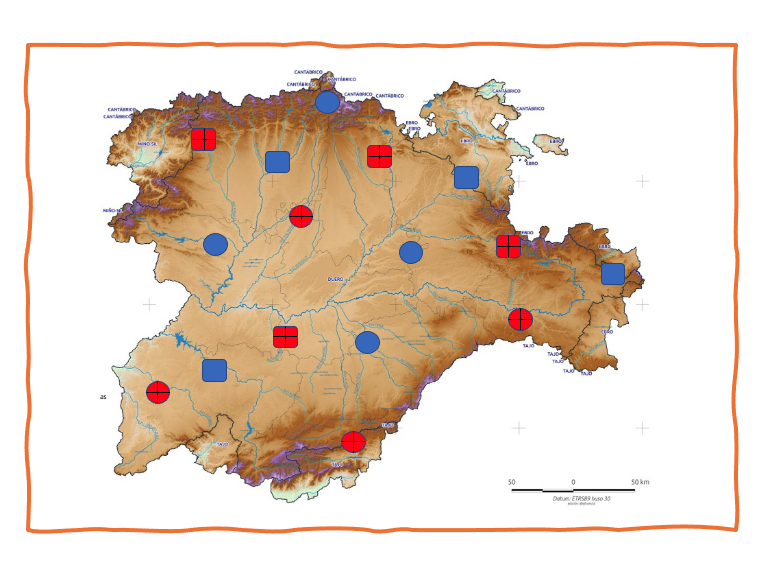

The sexual selection decree. Four populations were undivided monogamous (blue circles), another four divided monogamous (red circles), another four undivided polygamous (blue squares) and the remaining four populations were divided polygamous (red squares).

The above legend is false, of course, but imagine that it was true and now, in the 21st century and after over 40 generations of different selective pressures in those populations, we could answer questions such as: Are the individuals in the different cities different in any way? Has a history of relaxed or intense sexual selection and/or population subdivision shaped morphological, physiological or behavioural traits in males and females? Have these different histories related to sexual selection intensity affected the viability of populations?

These are some of the questions that we are addressing in our lab using a humble but useful and interesting study system, Callosobruchus maculatus, a pest beetle of stored legumes that is popular in studies of the evolutionary ecology of sexual selection and sexual conflict. In particular, in our latest study in Evolution Letters we focused on whether selection history associated to mating system (monogamy/polygamy) and the presence or absence of population subdivision and connectivity (known as metapopulation structure) modulated sexual conflict dynamics. Sexual conflict occurs when the interests of males and females over mating and reproduction (or parental care in some species) differ. In recent decades it has become obvious that this conflict of interest between the sexes is widespread in the animal kingdom, from insects to humans, and that it has far-reaching evolutionary implications.

Callosobruchus maculatus mating pair. Photo: Eduardo Rodriguez-Exposito

So, using C. maculatus, a species endowed with some of the best examples of sexual conflict traits, including a remarkable spiny intromittent organ in the male genitalia that damages the female reproductive tract during copulation, we did something similar to the made-up legend above. Why did we do it? Not simply because we could, but because this kind of experimental evolution can provide important insights into the drivers and modulators of sexual interactions. In a study spanning over 40 generations under the conditions described above (enforced monogamy vs free polygamy added to the presence or absence of population subdivision and migration among subpopulations), we ran several assays to inspect the consequences of mating. We did this by mating standard tester individuals from outside the selection experiment to individuals from the different experimental populations (undivided monogamous, divided monogamous, undivided polygamous and divided polygamous), and checking longevity and reproductive success trajectories.

Most research on the evolution of sexual conflict has been conducted using simple population scenarios (for instance, in the absence of population spatial structure), or uniform environments, but our study challenged these traditional empirical undertakings. What made our study unique is that we additionally imposed selection arising from metapopulation structure.

The results of this study, co-authored by Eduardo Rodriguez-Exposito, support traditional sexual conflict theory by showing that females from populations with a history of intense sexual selection and sexual conflict evolve higher resistance to male harm, and that enforced monogamy leads to the evolution of less resistant females. However, our study uncovered that this pattern of antagonistic coevolution between the sexes is reversed in spatially structured populations. These findings indicate that the ecological and demographic context moderates the consequences of sexual antagonism.

This discovery has important implications for aspects of sexual selection, population dynamics, conservation biology and pest control. We hope our study will spur further theoretical and empirical research focusing on the interplay between ecology and evolution in defining male-female interactions.

Dr Francisco (Paco) Garcia-Gonzalez is a Senior Research Scientist at Doñana Biological Station-CSIC (Spanish Research Council) and an Adjunct Research Fellow at the Centre for Evolutionary Biology (The University of Western Australia). The original article is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.