A new study published in Evolution Letters has shown that female fruits flies can alter their reproductive behaviour to exert control over paternity success of different males. Lead author Dr Meghan Laturney tells us more.

Sexual relationships can be very complicated. Part of this complexity is born out of the fact that sexual reproduction, like any social behaviour, is a combination of both cooperation and conflict. From an evolutionary perspective, sex is fundamentally a cooperative behaviour. The only way for a sexually reproducing individual to have any reproductive success is to make offspring; and in most cases this requires copulation with the appropriate social partner. When males and females copulate, both the individual and their partner are working towards a collective goal: to produce offspring together to result in increased personal reproductive success. Copulation is cooperation since it results in mutual gain.

However, it’s not just about getting some reproductive success – it’s about maximizing your reproductive success. One common way to increase either the quantity or quality of offspring produced is to mate more often with different partners. In general, this is true for both males and females and applies to various species across the animal kingdom. Even in groups that are socially monogamous (males and females pair bond and raise young together), many offspring are produced from non-pair bonded parents, suggesting that sexual promiscuity is the rule rather than the exception. Females, however, are limited in the number of offspring they can produce by the number of eggs they develop – a restraining factor not shared with males. This makes it much more likely that female remating (polyandry) is advantageous because it increases the genetic diversity of the brood (group of offspring) rather than a bump in brood number.

But how does this increased sexual behaviour impact the offspring production of previous mates? Well, it depends heavily on the species’ mating system; however, generalizations can be made. It’s often the case that although male remating (polygyny) has little impact on the success of females, polyandry on the other hand significantly lowers the siring capability of her previous male mates. This makes sense when we are reminded that when females remate in quick succession, the sperm of her mates will coexist within the same reproductive tract competing for fertilization of a limited number of eggs. Putting it together, polyandry presents a conflict between the sexes as it is beneficial for females but costly for males.

In the face of sexual conflict, males are predicted to develop ways to increase their offspring production. That means if females are going to remate, then males should be prepared to compete for fertilization success within female reproductive tract. Indeed, many researchers have reported instances of tactics of sperm competition: characteristics expressed by the male or the sperm that increase the chances of his sperm fertilizing the egg. As a result of sperm competition, brood paternity of a multiply-mated female is not equal across mates. In fact, a likely outcome for many vertebrate and invertebrate species alike is a bias in brood paternity in favour of the last male, a phenomenon known as last male sperm precedence. In other words: one male wins or at least wins majority. Although this outcome is rather ideal for the last male, it also results in an overall reduction in the brood genetic diversity, which is hypothesised to be a benefit to the female and a driving factor for the prevalence of polyandry.

Following the logic that suggested the development of male tactics of sperm competition, sexual conflict theory would also suggest that females develop counter-adaptations to reduce last male sperm precedence and restore maximum diversity. However, there has been very little attention on female control of reproduction. Unlike other systems that show similar co-evolution such as parasite-host interactions or plant-herbivore interactions, the arms race between males and females over the control of reproduction has been largely overlooked. Our recent work in Evolution Letters attempts to address this issue.

We focussed our efforts on understanding if females were capable of reducing last male sperm precedence. We used the model organism Drosophila melanogaster, better known as the fruit fly. Not only are insects easy to work with and have a fast reproductive cycle making them ideal for such an experiments, but also information of female reproduction in this species would complement a large body of knowledge that already exists on the male traits documented to evolve via sexual conflict.

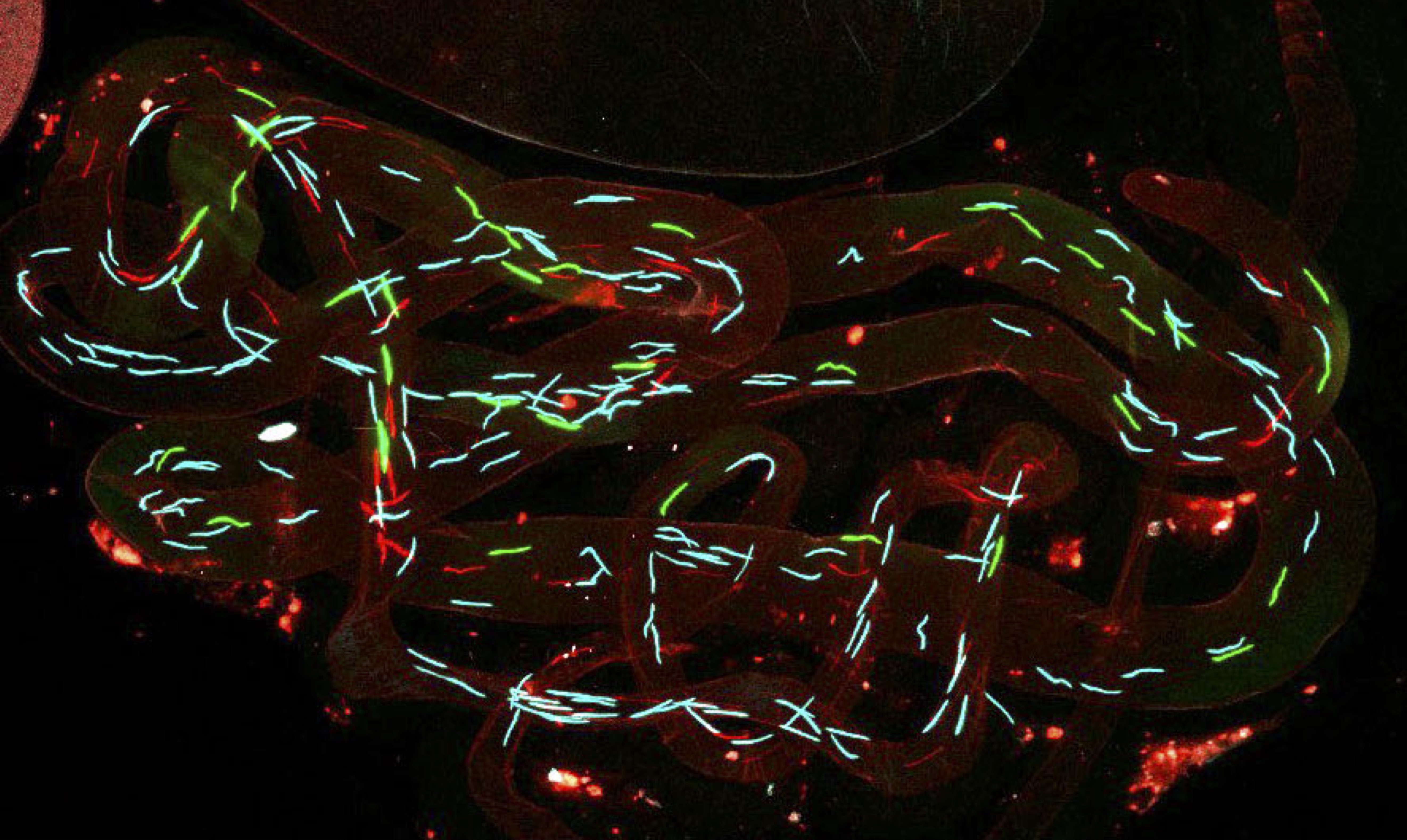

Using molecular cloning techniques established in the field, we developed male fruit flies that express either a green, red, or blue fluorescent protein on the head of their sperm. When females mate these males we can track the sperm within the reproductive tract and the paternity of the offspring. We exposed females to these genetically modified males and recorded how many times females mated and with which male. We then compared the patterns of sperm storage as well as patterns of paternity to the patterns of mating behaviour. We found that females varied in the amount of both last male sperm precedence and remating rate. When we investigated this variation we found that the degree of last male sperm precedence depended on the mating rate of females: females that mated with more males and in quick succession showed a decrease in offspring from the last male and consequently a more equally shared brood paternity.

From our experiments we find that females are not necessary defenceless when it comes to the tactics that males have developed to maximize male reproductive success. Females can counter last male sperm precedence by modulating their mating rate in order to maximize the genetic diversity of their brood and ultimately their own personal reproductive success.

Our results provide further evidence for a growing body of work establishing that females exert control over their reproduction even after copulation – a capability previously reserved for males and sperm competition. Work on sexual conflict in this species allows us to further our understanding of not only the principles that govern offspring production and sexual behaviour but also identify the mechanisms that make this behaviour possible. Although sexual relationships will always be complicated, experiments like ours explore the factors that muddy the waters. One co-evolutionary arms race at a time.

Dr Meghan Laturney is lead author on the study, which was carried out at the University of Groningen. The paper is freely available to read and download here.