It’s here! The first issue of our exciting new evolutionary biology journal is now online, featuring sex, sperm, speciation, and more! All papers are available to read right now, fully open access, via the Evolution Letters website

Here is what our inaugural issue has in store…

Photo © Bart Zijlstra – www.bartzijlstra.com

Overview

- The two-fold cost of sex was first proposed by Maynard Smith, who pointed out that sexual females must spend 50% of their resources on making sons, but those sons will produce no offspring themselves. As a result, asexual lineages should outcompete sexual lineages. Maynard Smith’s theory raised one of the most interesting questions in evolutionary biology: why is there sex?

- To date, the cost of sex has not been directly estimated, so this popular idea has remained untested for over 40 years.

- In this new study, Gibson et al. provide the first estimate of the cost of sex by measuring frequencies of sexual and asexual snails in natural, mixed populations.

- They show that the increased frequency of asexuals closely matches that predicted by a two-fold cost, validating foundational theory in evolutionary biology.

Read the study in full here.

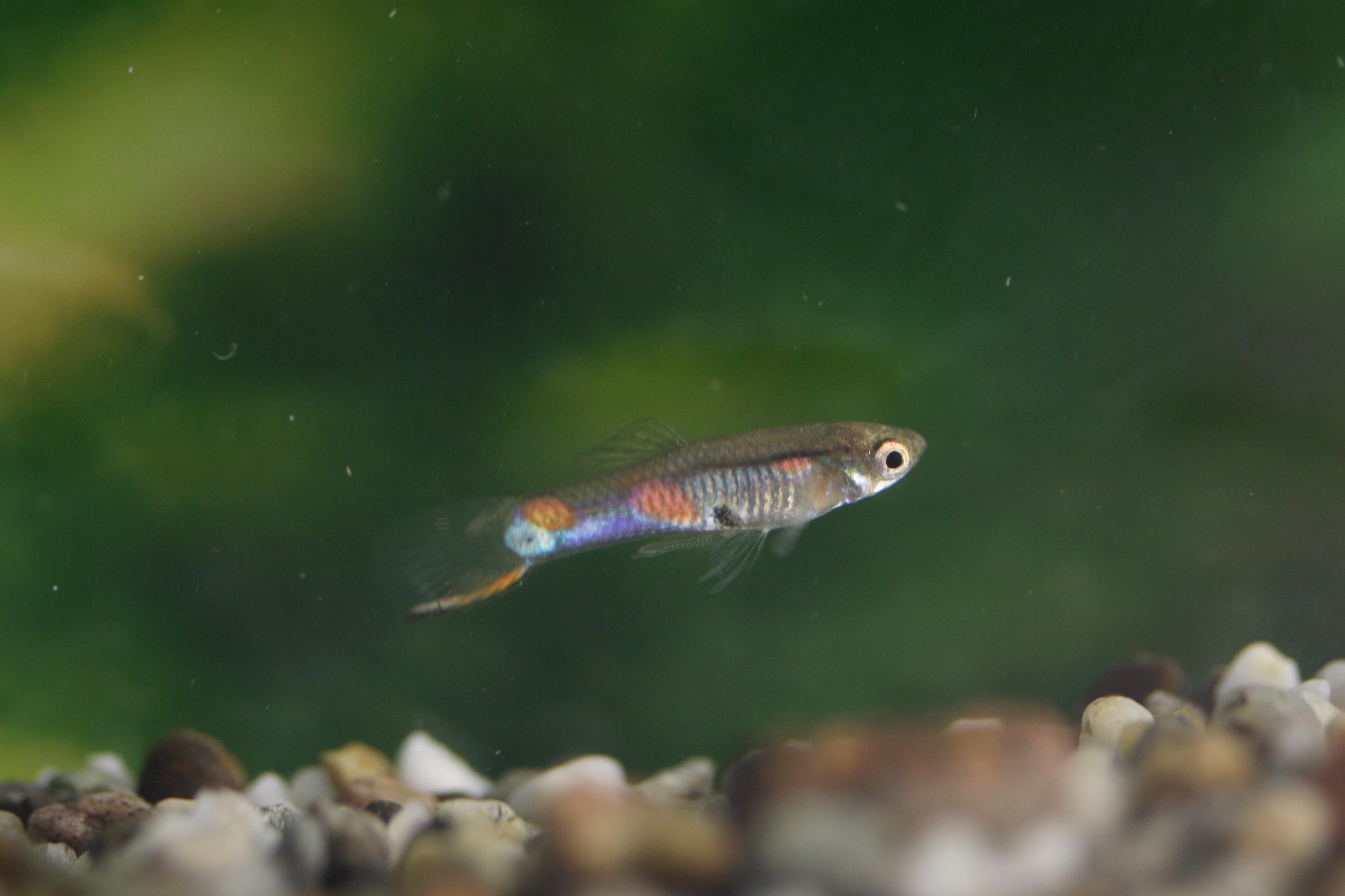

Photo © Clelia Gasparini

Overview

- Delays between gamete production and fertilisation are inevitable in internally fertilising species, and males often have to store sperm in their reproductive tract while they seek out copulations.

- Gasparini et al. show that in guppies, old sperm (i.e. those stored by the male for longer durations before ejaculation) are not only at a disadvantage in sperm competition, but also produce sons with slow-swimming sperm.

- Males that stored sperm for longer before inseminating females had a greater number of slow swimming sperm and lower paternity success in competitive insemination trials.

- Fascinatingly, sons produced by these males also had slow swimming sperm, demonstrating that sperm (or seminal fluid) ageing may have considerable transgenerational effects.

Read the study in full here.

Photo © Ben Ammon

Overview

- Although there have been many estimates of selection in natural populations, studies have rarely examined both spatial and temporal dynamics at the same time, especially across different life history stages.

- Here, Wadgymar et al. assess spatial and temporal patterns of natural selection in the subalpine perennial forb Boechera stricta, using experimental gardens across a steep environmental gradient, to test the hypothesis that natural selection fluctuates around local phenotypic optima.

- Boechera stricta was found to exhibit significant genetically-based clines in physiological, morphological, and phenological traits, with intermediate trait values being favoured – providing evidence for stabilising selection.

- Genetically-based clines are likely to have evolved in response to long-term spatial variation in selection across steep elevational gradients.

Read the study in full here.

Photo © Dan Greenberg

Overview

- Amphibians exhibit one of the highest rates of modern extinction of all vertebrates.

- By examining evolutionary patterns of modern extinction risk across more than 300 amphibian genera, Greenberg & Mooers show that lineages with high ongoing diversification are at greater risk of extinction than slowly diversifying lineages.

- This supports the idea that lineages that speciate readily may also lose species readily, due to characteristics that promote both speciation and extinction (e.g. specialisation and isolation).

- From a conservation perspective, this clustered extinction threat means that protecting a relatively small number of species may go a long way towards preserving amphibian phylogenetic diversity.

Read the study in full here.

O’Brien & Wolf: The coadaptation theory for genomic imprinting.

Photo © W.H. Calvin

Overview

- Genomic imprinting is a peculiar phenomenon occurring in a subset of genes, where the expression of each gene copy depends on whether is came from the mother or father.

- Here, O’Brien & Wolf address the question of why genomic imprinting evolved, using a simple mathematical model where an animal’s success in social interactions depends on the combination of its own traits, and those expressed by the animals it interacts with.

- The study shows that when the relatedness of interacting animals differs through their maternally and paternally inherited genes, selection favours expression of the gene through which relatedness is higher. This enhances the compatibility of the genes expressed by both individuals.

- O’Brien & Wolf’s general coadaptation theory demonstrates that genomic imprinting can evolve because it coordinates the traits of interacting animals. leading to more successful social interactions.

Read the study in full here.

Finally, don’t miss Editor-in-chief Jon Slate’s introduction to the journal, telling the story of how Evolution Letters came to be, and outlining our vision for the future. We hope you enjoy our first issue.

2 Comments

[…] can find the open-access article here, plus commentary on the Evolution Letters […]

[…] can find the open-access article here, plus commentary on the Evolution Letters […]