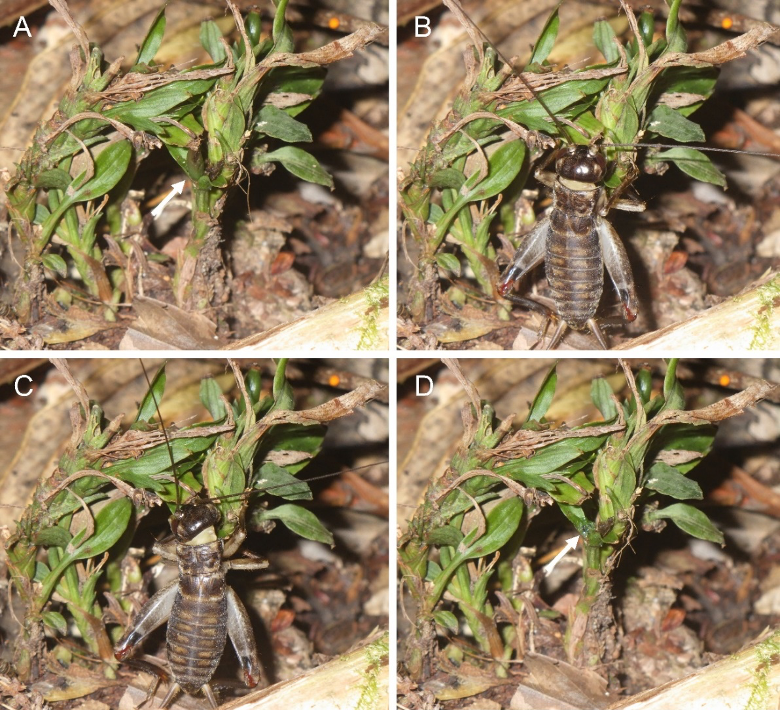

A new study published in Evolution Letters presents evidence of the apparently unusual seed dispersal system by crickets and camel crickets in Apostasia nipponica (Apostasioideae), acknowledged as an early-diverging lineage of Orchidaceae. Lead author Dr. Kenji Suetsugu tells us more.

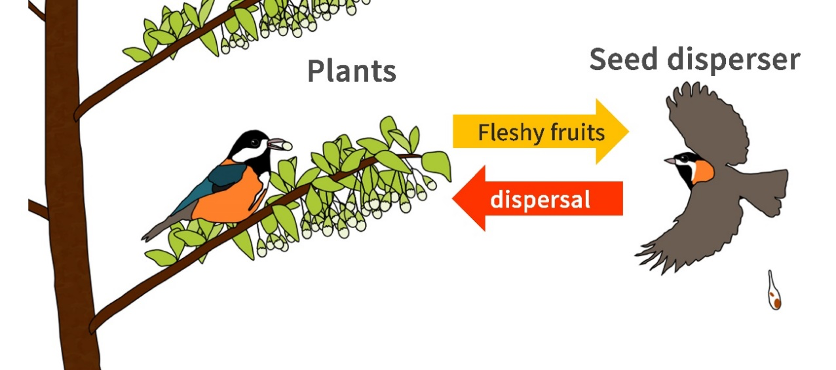

Seed dispersal is a key evolutionary process and a central theme in terrestrial plant ecology. Animal-mediated seed dispersal, most frequently by birds and mammals, benefits seed plants by ensuring efficient and directional transfer of seeds without relying on random abiotic factors such as wind and water. Seed dispersal by animals is generally a coevolved mutualistic relationship in which a plant surrounds its seeds with an edible, nutritious fruit as a good food for animals that consume it. Birds and mammals are the most important seed dispersers, but a wide variety of other animals, including turtles and fish, can transport viable seeds. However, the importance of seed dispersal by invertebrates has received comparatively little attention. Therefore, discoveries of uncommon mechanisms of seed dispersal by invertebrates such as wetas, beetles and slugs usually evoke public curiosity toward animal–plant mutualisms.

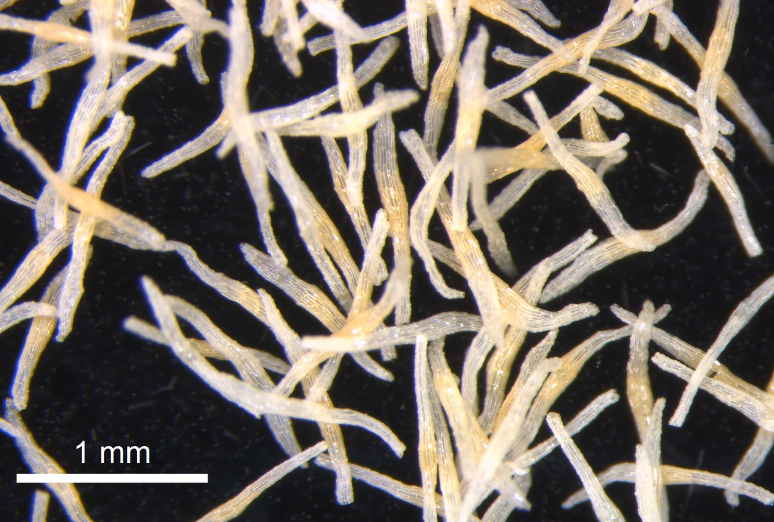

Unlike most plants, all of the >25,000 species of orchids are heterotrophic in their early life history stages, obtaining resources from fungi before the production of photosynthetic leaves. Orchid seeds, therefore, contain minimal energy reserves and are numerous and dust-like, which maximizes the chance of a successful encounter with fungi in the substrate. Despite considerable interest in the ways by which orchid flowers are pollinated, little attention has been paid to how their seeds are dispersed, owing to the dogma that wind dispersal is their predominant strategy. Orchid seeds are very small and extremely light, and are produced in large numbers. These seeds do not possess an endosperm but instead usually have large internal air spaces that allow them to float in the air column. In addition, orchid seeds are usually winged or filiform, evolved to be potentially carried by air currents. Furthermore, most orchid seeds have thin papery coats formed by a single layer of non-lignified dead cells. It has been thought that these fragile thin seed coats cannot withstand the digestive fluids of animals, in contrast to the thick seed coats in indehiscent fruits, which are considered an adaptation for endozoochory.

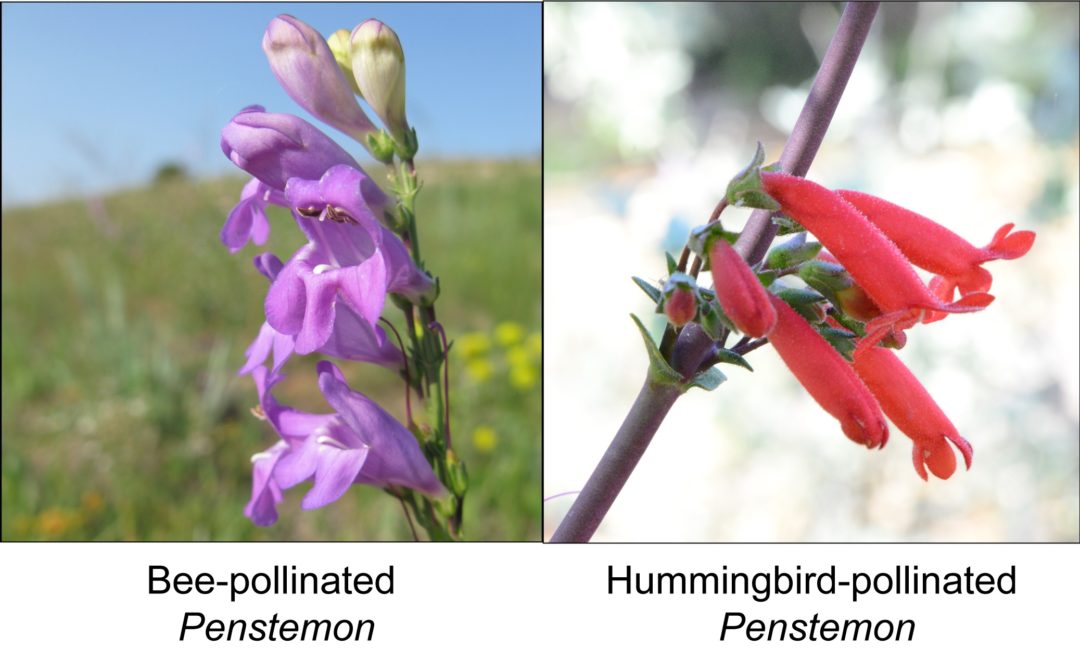

However, it is noteworthy that the subfamily Apostasioideae commonly has indehiscent fruits (which don’t split open when ripe) with hard, crustose black seed coats. Apostasioids are the earliest-diverging subfamily of orchids and consist of only two genera (Apostasia and Neuwiedia), with only ~20 species distributed in southeastern Asia, Japan, and northern Australia. All Apostasia and most Neuwiedia species investigated to date are known to possess berries with hard seed coats. Apostasioids are also well known for several unique traits, such as a non-resupinate flower (i.e. it doesn’t twist when opening) with an actinomorphic perianth (radially symmetrical outer part of the flower) and pollen grains that do not form pollinia. These have been considered ancestral characteristics in orchids, given that they are similar to those found in the members of Hypoxidaceae (which is closely related to Orchidaceae) family. Similarly, the presence of an indehiscent fruit with a thick seed coat, found in most Apostasia and Neuwiedia species can be an ancestral trait in orchids.

Here I have studied the Apostasia nipponica (Apostasioideae) seed dispersal system in the forest understory of the warm-temperate forests on Yakushima Island, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. Consequently, I present the evidence for seed dispersal by crickets and camel crickets in A. nipponica. Similar results were obtained in different years, indicating that this interaction is likely stable, at least in the investigated site. It probably constitutes a mutualism, wherein both partners benefit from the association—orthopteran visitors obtain nutrients from the pulp and A. nipponica achieves dispersal of seeds from the parent plants. The seeds of A. nipponica are coated with lignified tissue that likely protects the seeds as they pass through the digestive tract of crickets and camel crickets. Although neither the cricket nor camel cricket can fly, they potentially transport the seeds long distances owing to their remarkable jumping abilities. Despite the traditional view that the minute, dust-like, and wind-dispersed orchid seeds can travel long distances, both genetic and experimental research has indicated that orchids have limited dispersal ability; orchid seeds often fall close to the maternal plant (within a few meters), particularly in understory species. Given that A. nipponica fruits are produced close to the ground in dark understory environments where the wind speed is low, seed dispersal by crickets is probably a successful strategy for this orchid.

Orchid seeds lack a definitive fossil record due to their extremely minute size. Therefore, the interaction described here provides some important clues as to the animals that may have participated in the seed dispersal of the ancestors of orchids. Given that the origin of crickets and camel crickets precedes the evolution of orchids, they are among the candidates for seed dispersers of the ancestors of extant orchids. Owing to many plesiomorphic characteristics and the earliest-diverging phylogenetic position, members of Apostasioideae have been extensively studied to understand their floral structure, taxonomy, biogeography, and genome. However, there is still a lack of information regarding seed dispersal in the subfamily. In this paper, I have documented the animal-mediated seed dispersal of Apostasioideae members for the first time. Whether seed dispersal by animals (and particularly by orthopteran fruit feeders) is common in these orchids warrants further investigation. It is possible that this method of dispersal is an ancestral trait in Apostasioideae, given that indehiscent fruits with a hard seed coat are common within the clade. Further research, such as an ancestral character-state reconstruction analysis of more data on the seed dispersal systems of other apostasioids, can provide deeper insights into the early evolution of the seed dispersal system in Orchidaceae.

Dr. Kenji Suetsugu is Associate Professor at Kobe University, Japan. The original study is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.