A new study in Evolution Letters sheds light on why certain species are more likely to hybridize than others. Here, lead author Dr. Nora Mitchell explains her findings.

The phenomenon of hybridization has long-fascinated botanists and is a primary research focus in our lab group. Plants are notorious for their often-promiscuous mating habits and ability to produce viable offspring with other species. Investigations into specific lineages have documented the ways in which hybridization can contribute to evolutionary processes such as adaption, speciation, and biological invasion, but these examples may not be representative of all plants. Some plant groups tend to hybridize frequently, while other groups tend to hybridize rarely or not at all. There is a lack of information regarding why plant groups hybridize at different rates, especially at the global scale. For instance, do plants with certain life history strategies or pollination syndromes tend to hybridize more frequently than others? In a new study in Evolution Letters, we looked for patterns between rates of hybridization and eleven different traits in plants across the world.

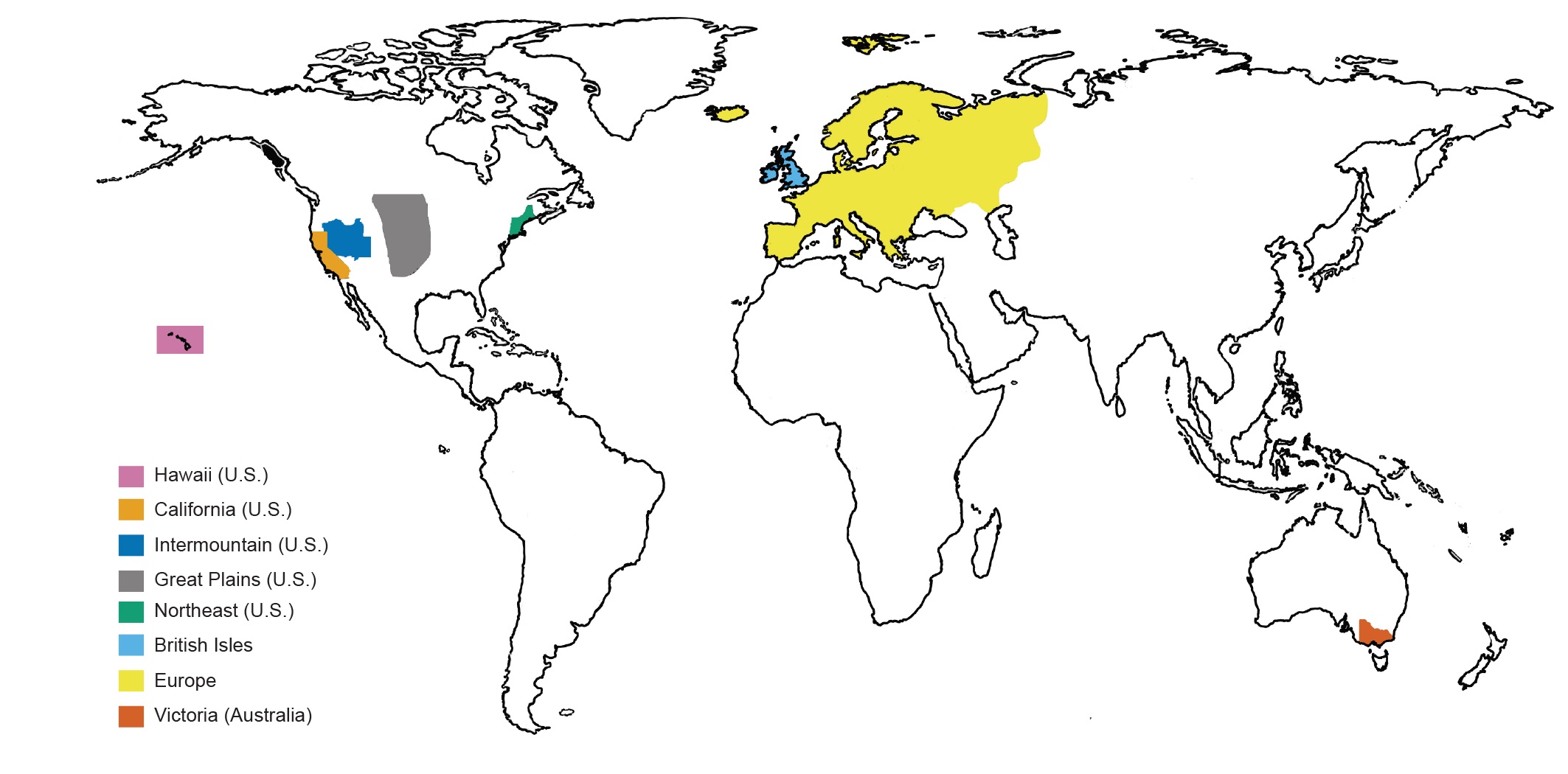

There are an estimated 400,000 species of vascular plants (those with a developed transport system, including ferns, conifers, and flowering plants), so it was not logistically feasible to collect data on each species. Instead, we harnessed the power of floras (published works that document plant life) to analyze a subset of regions. We scanned floras from North America, the Pacific Islands (Hawai’i), Europe, and Australia, and counted the number of documented cases of hybrids and nonhybrid species found in each region. Using these data, we calculated two hybrid indices based on the number of hybrids relative to nonhybrids at the genus and family levels. We also gathered information on eleven different traits with either theoretical or empirical evidence relating them to hybridization, including aspects of life history, growth form, reproduction, environment, and genome size, from the floras and additional sources.

In total, we collected hybrid data and trait information on 195 vascular plant families and 1772 vascular plant genera. Our goal was to see if there were relationships between any of our eleven traits and hybridization rates. We incorporated information from published phylogenetic trees to account for relatedness between groups and ran individual models to analyze potential trait × hybrid relationships.

We found several intriguing results using different combinations of taxonomic levels and measures of hybridization. Our most striking finding was that plant groups dominated by perennial species (those that live for more than one year) tended to have more hybrids than those dominated by annual species (those that live a year or less). Additionally, groups with woody growth forms tended to have more hybrids, and sometimes groups with non-living pollinators and higher rates of outcrossing also tended to have more hybrids.

We proposed that these associations could be due to some combination of factors that promote the formation of hybrids or factors that promote the persistence of hybrids. For instance, plants that disperse their pollen via the wind may have a better chance of mating with a different species, enabling them to form hybrids, while those that rely on insects may not have as many opportunities to do so. Likewise, long lifespans in perennial groups may allow them to have high reproductive output over time despite being partially sterile, enabling the hybrid lineages to persist. Although these observational patterns do not imply a causal mechanism, they can serve as a basis for further experimental work investigating how and why these traits are linked to hybridization, and their evolutionary consequences both in the past and in the future in a changing world.

Dr. Nora Mitchell is Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire. The original article is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.