A new study published in Evolution Letters dissects the complex processes and interactions between the sexes that determine which male fathers the offspring when females have mated with different males. Here, lead author Stefan Lüpold explains the motivation for, and key conclusions of, the study.

Students of evolutionary biology will at some point encounter sexual selection, a potent and pervasive selective force driving the evolution of traits for the sole purpose of influencing the reproductive success of their bearers. We learn that males compete for access to females, with the strongest or best-armed males having an edge over their competitors, or that females choose males with the most elaborate adornment or most beautiful song as their mates. In other words, we learn that there is male competition on the one side, and female choice on the other—implying that these are two separate selective processes targeting different types of traits.

Indeed it is possible for males to compete over mating opportunities in the absence of females (e.g. via monopolizing resources that are then likely to attract females), and it is possible for females to sample different males before settling with one, without these males ever crossing paths. Hence, male-male competition and female choice could indeed be largely independent evolutionary processes, at least superficially. But it is also increasingly clear that many traits (e.g., birdsong) can serve both to attract females and to keep rivals at bay, thus suggesting some level of non-independence between the two forms of selection.

The separation of selection within and between sexes dissolves even more in the situation of post-mating sexual selection, which is not concerned with accessing mating opportunities but rather with fertilization success after a female has mated with more than one male. Female multiple mating is now well-documented throughout the animal kingdom and comes with real consequences: Successful mating no longer secures paternity of the offspring. Sperm from different males are likely to overlap in time and space, and so compete for fertilization. However, multiple mating also provides females an opportunity to influence paternity, especially if they have little choice before mating.

Although often considered an extension of the respective selective processes before mating, ‘sperm competition’ and ‘cryptic female choice’ might be even less separable than their premating counterparts. After all, the presence of sperm from different males, and so the competition between them, is a prerequisite of any female choice at the gamete level. Consequently, understanding post-mating sexual selection and how it selects on the traits involved requires detailed studies of the reproductive processes in the context of both male and female effects on their outcome. This is challenging because for most species we have limited knowledge of what traits even are the targets of post-mating selection, let alone of how exactly they contribute to variation in paternity. To make matters worse, when ejaculates—themselves complex and multi-faceted—operate within the female reproductive tract, each female tract might have its own selective conditions, affecting how these ejaculates function and compete.

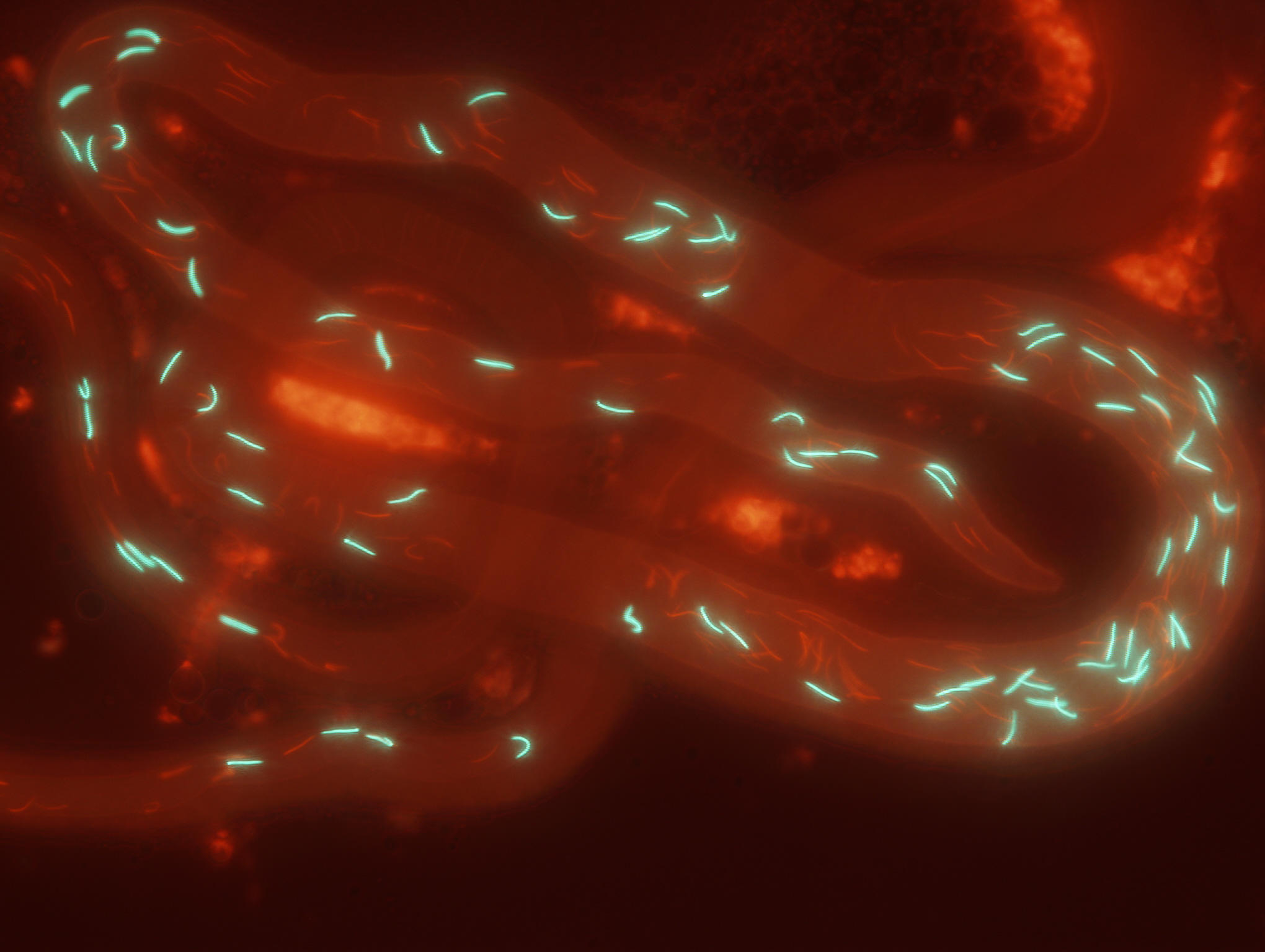

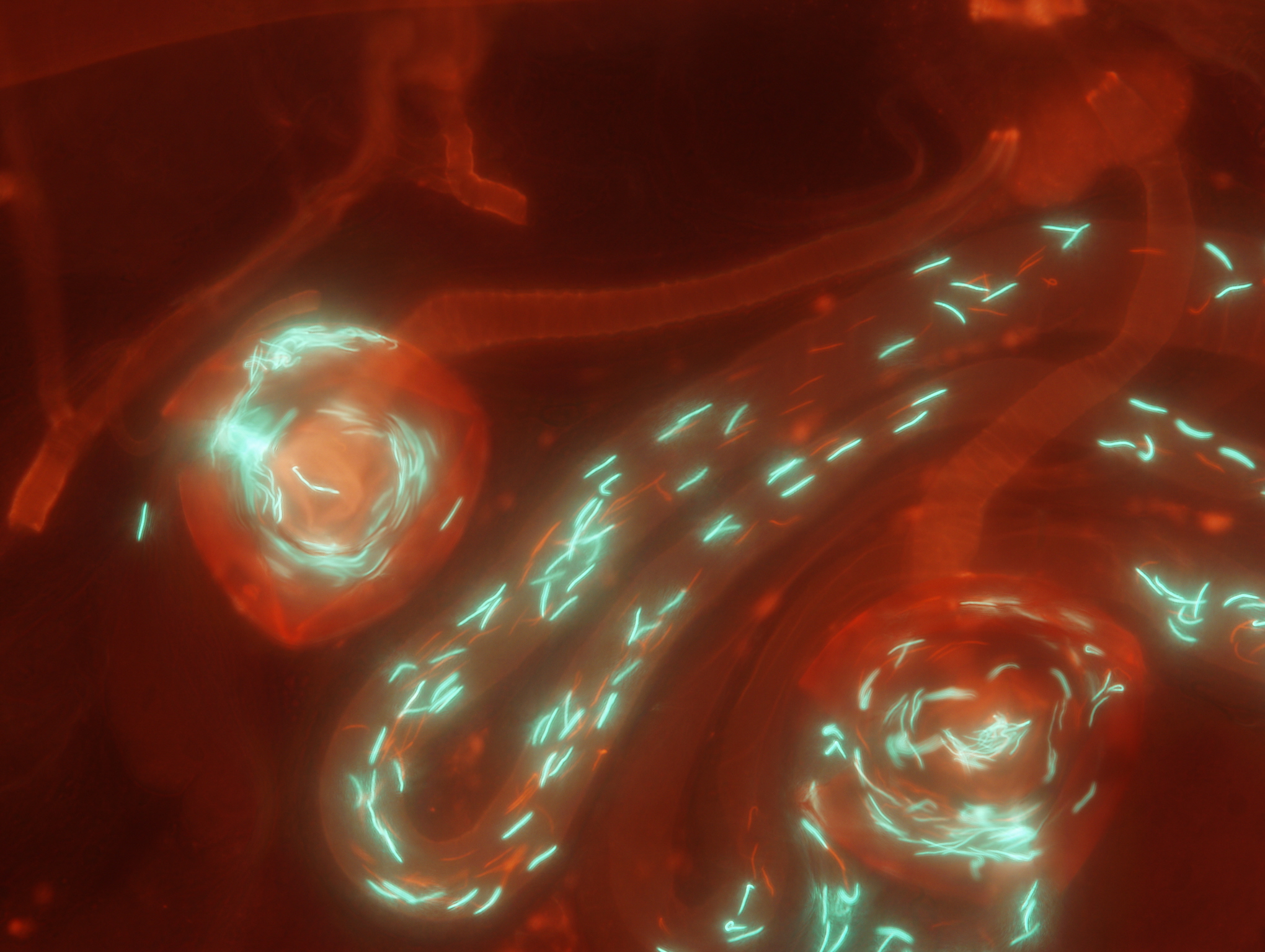

Fruit fly lines which express green or red fluorescent proteins in their sperm heads allow sperm from different males to be discriminated within the female reproductive tract.

Equipped with glow-in-the-dark sperm and inbred lines of Drosophila fruit flies that allowed us to visualize the processes within the female reproductive tract and replicate competitive matings among the same male and female genotypes over and over, we attempted to tease apart these complex processes of post-mating sexual selection. This endeavor required a three-stage approach: First, we determined how ejaculate traits themselves influence fertilization success by mating genetically identical females to pairs of males with different genotypes. These analyses revealed that larger numbers of longer (but slower-swimming) sperm are better at displacing rival sperm from the female sperm-storage organs and subsequently fertilizing eggs. Second, we identified if and how females might bias the reproductive outcome, holding competing male genotypes constant. Here, we found that females can bias sperm storage between males primarily by varying the timing of ejecting a mass containing excess second-male and displaced first-male sperm from their reproductive tract before starting to lay eggs. In the third stage, which is the focus of our article in Evolution Letters , we were now positioned to let the various female and male traits interact.

In this final installment, we again followed the fate of competing ejaculates through the different reproductive stages, competing sperm from different combinations of males across varying female backgrounds (i.e. female × male × male interactions). We identified two- and three-way interactions among female and male traits across different reproductive events, from sperm transfer to female sperm ejection and sperm storage (which is then proportional to paternity). All these observed interactions between sexes highlight just how intertwined sperm competition and cryptic female choice are. Viewing these two forms of selection as two extremes of a continuum would thus be far more appropriate than considering them separate processes.

Our experiment also revealed complex interactions between the lengths of competing males’ sperm and the primary female sperm-storage organ. These two sex-specific traits form an extreme example of co-evolution between male and female traits across Drosophila species. That this co-evolution largely results from a competitive advantage of longer sperm coupled with female biases that also favor longer sperm provides yet another piece of evidence that sperm competition and cryptic female choice are not independent. In fact, they can jointly target the same trait. Importantly, this co-evolution also indicates that complex interactions between the sexes are not getting in the way of directional sexual selection. Rather, in modest form, they might even fuel it by maintaining genetic variation that would be depleted by directional selection alone.

Clearly, our study represents just a first attempt at disentangling the complex interplay of a few critical reproductive traits and processes. Just imagine how complicated, but also how fascinating, it would be if we were to include all these other female and male traits that quite possibly interact in equally intricate ways!

Stefan Lüpold is an SNSF Professor in the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, University of Zurich, Switzerland. The original article is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.

The study was conducted in collaboration with researchers based in Switzerland and the United States, supported by both the Swiss and U.S. National Science Foundations.