The COVID-19 pandemic has been a stark reminder of the potential for new viral diseases to spread rapidly across the globe, causing widespread disruption to our health, medical infrastructure, and economies. SARS-CoV‑2 is the latest in a long line of viruses that have made the leap from wildlife into humans, following in the footsteps of the likes of HIV and pandemic H1N1 (1918), and many other major diseases whose emergence predates modern science. These events have sparked growing interest in predicting which viruses currently circulating in animals have the potential to transmit to humans and cause future outbreaks, and which hosts, or host species are the most likely donors of the next pandemic.

Conducting experiments in the many vertebrate species involved in the evolution and spread of these viruses is impractical. Instead, our approach to study how viruses shift between host species makes use of a model system composed of many different species of fruit fly (Figure 1). Although fruit flies share many aspects of their antiviral immunity with vertebrate innate immunity, the main utility of this system is that it allows for large-scale experiments across a diverse panel of host species who last shared a common ancestor ~50 million years ago.

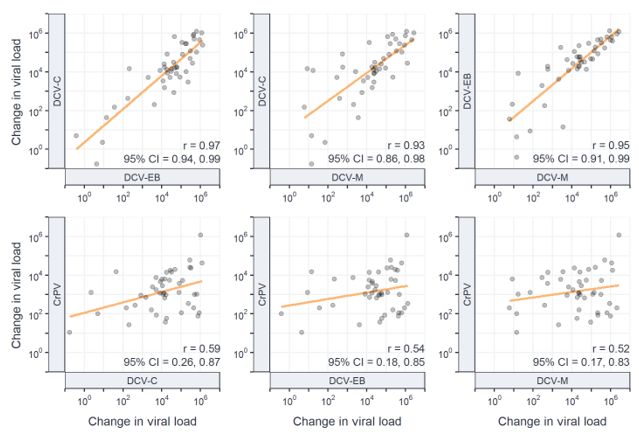

In a previous study (also published in Evolution Letters), we measured the extent to which fruit fly species susceptible to one virus are also susceptible to other, closely-related viruses, using experimental infections of three strains of Drosophila C virus (DCV) and one strain of the closely-related cricket paralysis virus (CrPV, Figure 2). One of our expectations from the study was that the phylogenetic correlations in susceptibilities across host species would be strongest between the two most closely related virus isolates (“DCV‑C” and “DCV-EB”), and weakest when comparing between the two virus species.

While this may seem obvious, what was unknown at the start of the study was the extent to which the strength of correlation would deteriorate as the evolutionary distance between pairs of viruses increased. Given there are many examples of virus phenotypes changing as a result of small changes in their genomes, the ~55% amino acid identity between DCV and CrPV may have been enough to erode any correlations that may be detectable between the three DCV isolates (which share 92–98% amino acid identity). Our findings showed that positive correlations were detectable between all pairs of viruses tested, and that correlation strength deteriorated in a stepwise fashion with increasing evolutionary distance between viruses (Figure 3).

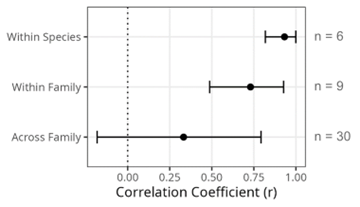

These findings left a remaining question: are correlations between viruses also detectable across greater evolutionary distances? For example, between viruses of different families, or even different genome classifications. Positive correlations at these scales may be a result of highly generalized host immunity, whereby selection by one virus results in increased resistance to other viruses. Alternatively, negative inter-specific correlations (or “trade-offs”) could exist, where host species that have evolved increased resistance to one type of virus have decreased resistance to another virus.

To explore these possibilities, we performed experimental infections across 35 host species using a larger panel of 11 different virus isolates, covering seven unique species, six families, and including nine +ssRNA viruses, a dsRNA virus, and a dsDNA virus. This provided us with 55 unique comparisons between pairs of viruses, 30 of which demonstrated positive inter-species correlations in viral load. The remaining 25 correlations were all indistinguishable from zero, with no evidence of any trade-offs in virus susceptibility across species. Extending the stepwise patterns we originally observed in our previous study, the strength of correlations was highest for viruses from within the same species, then decreased when comparisons were made within the same family, and was lowest when looking at viruses of different families (Figure 4).

So, what can these findings, and indeed studies of invertebrate hosts, tell us about the viruses that may one day pose a risk to humans? The number and diversity of viruses that exist in nature is staggering, and it is quite impossible to characterize them all through experiments like the ones conducted here. To assess whether a virus is indeed a threat we need to know if it can successfully infect humans, but we also need to know what its likely transmissibility and virulence will be. The existence of positive correlations in among host susceptibility between viruses, even those from different families or genome classifications, tell us that host susceptibility to one virus can also inform us about susceptibility to other viruses, sometimes even ones that are distantly related. In future, and with a much greater understanding of the patterns of susceptibility across hosts and their viruses, we may be able to infer the risk of novel viruses from something as accessible as their genome sequences.