It comes as no surprise that the environment in which an individual lives can have significant impact on its health and chances of survival. For example, animals are more likely to die over winter due to extreme cold or lack of available food.

Less obvious, however, are the effects of inbreeding. When related individuals’ mate, their offspring are described as inbred and are often worse quality compared to non-inbred individuals – a phenomenon known as inbreeding depression. There are many well-known anecdotal examples in human history, such as the Habsburg dynasty and the ancient Egyptian pharaohs, where marrying close relatives was a common occurrence. Incidentally, these marriages were often associated with high child mortality rates, which is likely more than just a coincidence.

Today, inbreeding depression is particularly concerning for small, endangered populations which may have no choice but to mate with a relative. This can result in low-quality offspring unlikely to survive and so threatens the persistence of these populations.

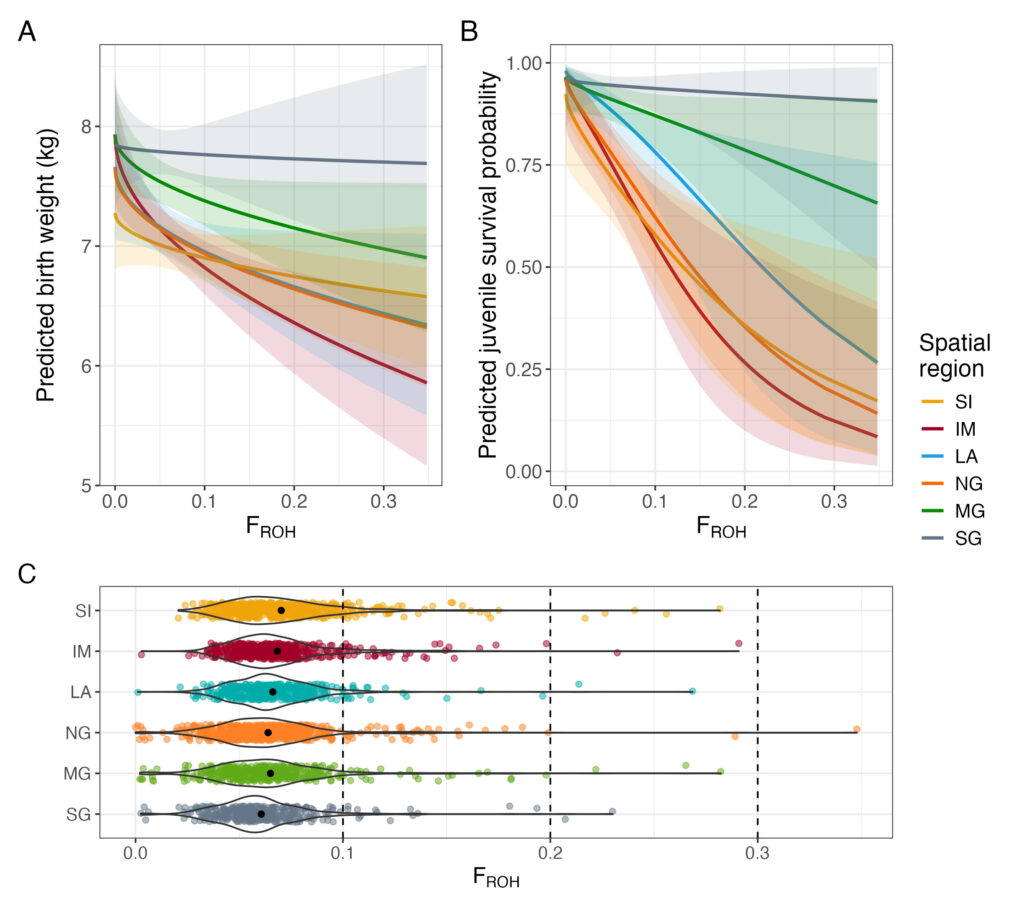

In our research, we investigated how spatial environment and inbreeding interact to affect survival in a wild population of red deer living on the Isle of Rum, Scotland. From past research, we know that survival differs drastically across our study area. In the harsher northern regions near the coast, low-quality grazing and competition make it difficult for calves to survive. At the same time, we know that this population suffers from inbreeding depression – very inbred calves are also less likely to survive.

Interestingly, in our study we showed that the effects of inbreeding depression are more severe in the harsher northern regions. Inbred calves in the north, are far more likely to die than their counterparts living in the south, where survival rates were generally higher, regardless of their inbreeding status. Our study is one of only a handful to show evidence for this interaction in a wild population, supporting several experimental studies.

These findings raise important questions for conservationists. If a captive population shows little impact of inbreeding depression, is this because it’s not experiencing the effects, or is it simply living in a forgiving environment? And what happens if these inbred individuals are released into the wild? Therefore, should conservation efforts be made to reduce inbreeding or improve the environmental conditions? There’s likely no “right” answer, but our study sheds new light on this complex issue. Understanding how the environment and inbreeding depression can interact may be crucial for managing small populations in the future, ensuring their long-term survival.