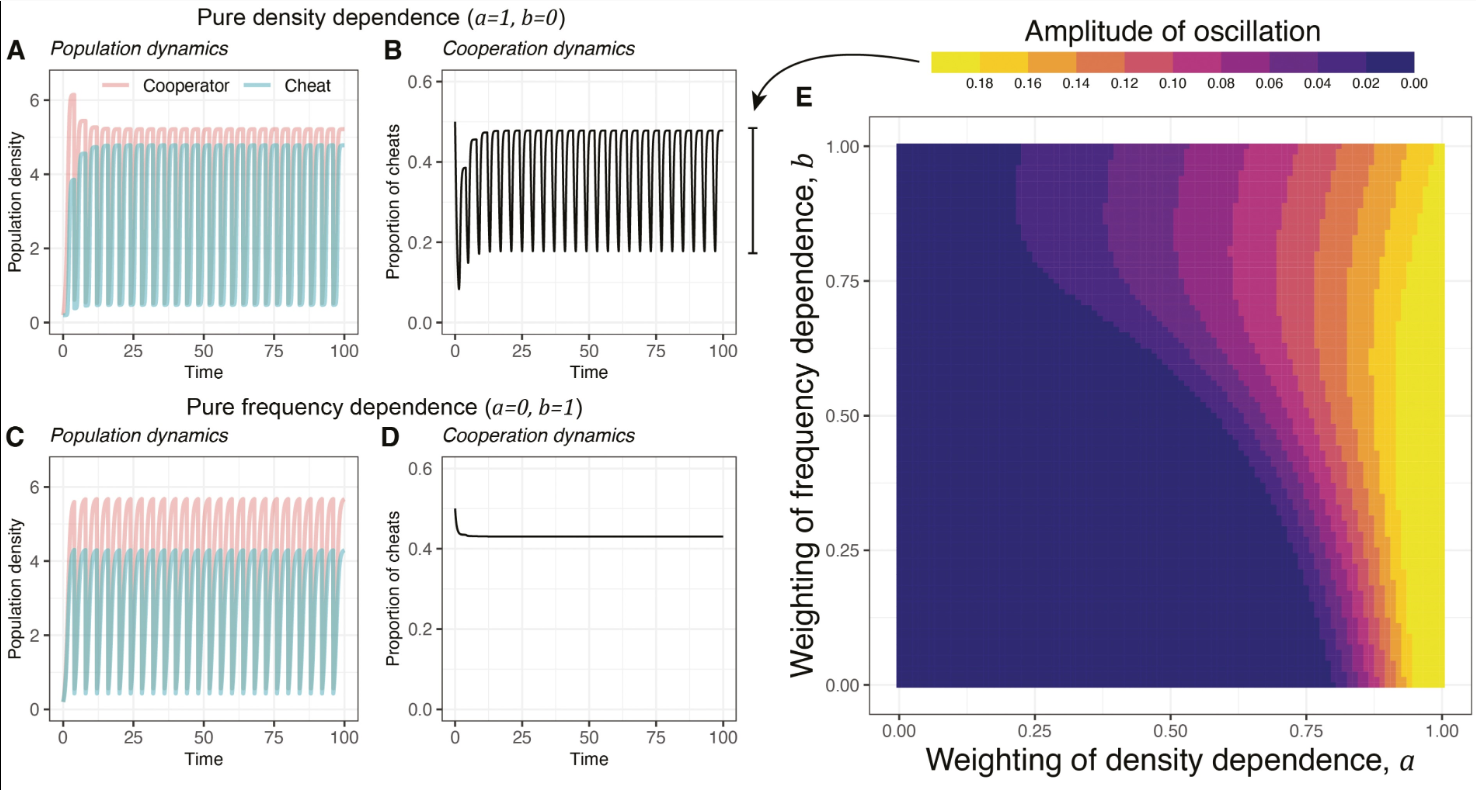

Recently, our paper on the dynamics in the proportion of cheats in a cooperative system was published in Evolution Letters. This paper explicitly considered (1) the common “serial passage” set up in experimental evolution, (2) the possibility of frequency and/or density dependence, and (3) random social group formation. We asked when can the proportion of cheats oscillate in the population dynamics, and how to get it or remove it in experiments? Our experience with the journal was very pleasant and we were lucky to have three positive referees, but that is not what I want to share with you in this blog. I would like to talk a bit about my experience in presenting the paper at the European Meeting for PhD Students in Evolutionary Biology (EMPSEB) before it was published. My motivation is that the organizing committee did an amazing job, and I wish more people to know about the conference, to compensate for my “cheating” behavior, which I will explain in this post.

Presenting theoretical projects is always a challenge. Besides the usual obstacles like nervousness on stage, and the stress of receiving critical questions, theoretical projects have its own additional difficulties. For instance, mathematical symbols can be intimidating and hard to understand for many people, but not explaining them would take the presentation off of a solid foundation and ignore the model assumptions. Another reason is that the information load is typically different for theoretical projects than in other subjects since the research question is more abstract. Similarly, some field biologists can feel that the theories are not tightly connected to the system they are studying and lose interest.

However, these exact challenges make a student conference an ideal place to experiment with different ways of presenting this science. The conference is organized by PhD students for PhD student attendees. There were about 80 attendees in 2023, with two parallel sessions where each presenter gave a 12-minute presentation. So, there is a large proportion of the conference who would listen to your talk and interact with you. In addition, the committee prepared anonymous notes for marking and suggestions, giving each presenter has a chance to reflect on our presentations. The crowd is very positive, and everyone is very engaged to hear what other PhD students are researching. This difference from conventional conferences made me decide to change some slides to let the audience become more involved.

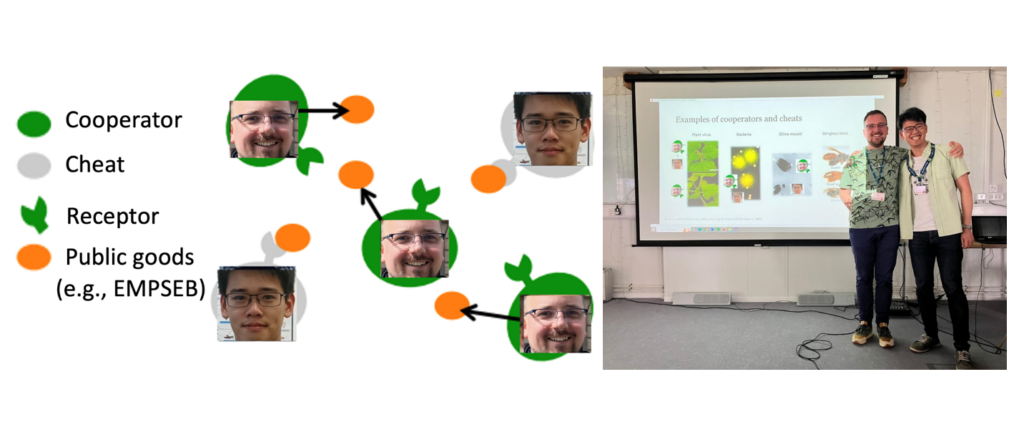

In my introduction slides, I had to explain the concept of cooperators and cheats in the context of social evolution, and show that they are common at all levels of biological organization. Because I wanted to make sure everyone was on board with me, I made a self-sarcastic cartoon that I am the cheater of a population, and one of the co-chairs of the conference committee, Viktor, is the cooperator (Fig. 1). The reasoning was that the committee members sacrificed their time and effort to make EMPSEB 28 happen, while I did nothing but enjoy the benefits of presenting the science. The audience loved it, and everyone could easily follow the examples on the later slides. Even though I went a bit over time later, I still got a lot of very positive feedback right after the presentation and during the conference, and about 60 constructive notes. And, maybe because my slide is the only one with committee members, I was lucky to get the best slide award of the conference.

Finally, I would like to take this opportunity to promote two things run by evolutionary societies: the Evolution Letters journal and the EMPSEB conference. While both of them are public goods, it is our decision to contribute and help make them better. And to all PhD students in evolutionary biology, I strongly recommend that you attend EMPSEB once, you will realize other students are facing similar challenges on the journey of PhD that we are not alone.