A new study published in Evolution Letters reveals that sex differences in maturation times arise in bird species where one sex is rarer and competes more strongly for mates than the other, supporting the prediction that sexual selection selects for delayed maturation. Here, lead author Dr. Sergio Ancona explains his findings.

The age at sexual maturation, that is the age when organisms are physiologically capable of breeding, is enormously variable across species and has pervasive impacts on fecundity, breeding behaviour and population numbers. Sex differences in age-to-maturation are both common and striking in nature, and although they have enchanted nature lovers for years, the causes of these differences are not fully understood. In my research group, we are fascinated by sex differences in general, and we find sex-differences in age-to-maturation particularly intriguing, as they may have important implications for sexual conflict and life history evolution. Seminal ideas by architects of modern evolutionary theory, notably R. Fisher (1930) and D. Lack (1968), are particularly inspiring for us. They proposed that intense sexual competition among males favours the evolution of delayed male maturation, since prolonged maturation may allow males to fully develop their capabilities for fighting, courting and breeding successfully. This alluring idea is often used to explain delayed male maturation relative to females in polygynous species (where one male mates with multiple females and each female only mates with a single male), but it has not been tested across a wide range of taxa. The interest in testing this hypothesis motivated our research. We, however, went a little beyond the conjectures of Fisher and Lack and incorporated a new element in our approach: we explored the impact of the social environment, as indicated by the adult sex ratio (usually expressed as the proportion of males in the adult population), on the evolution of sex-differences in age-to maturation.

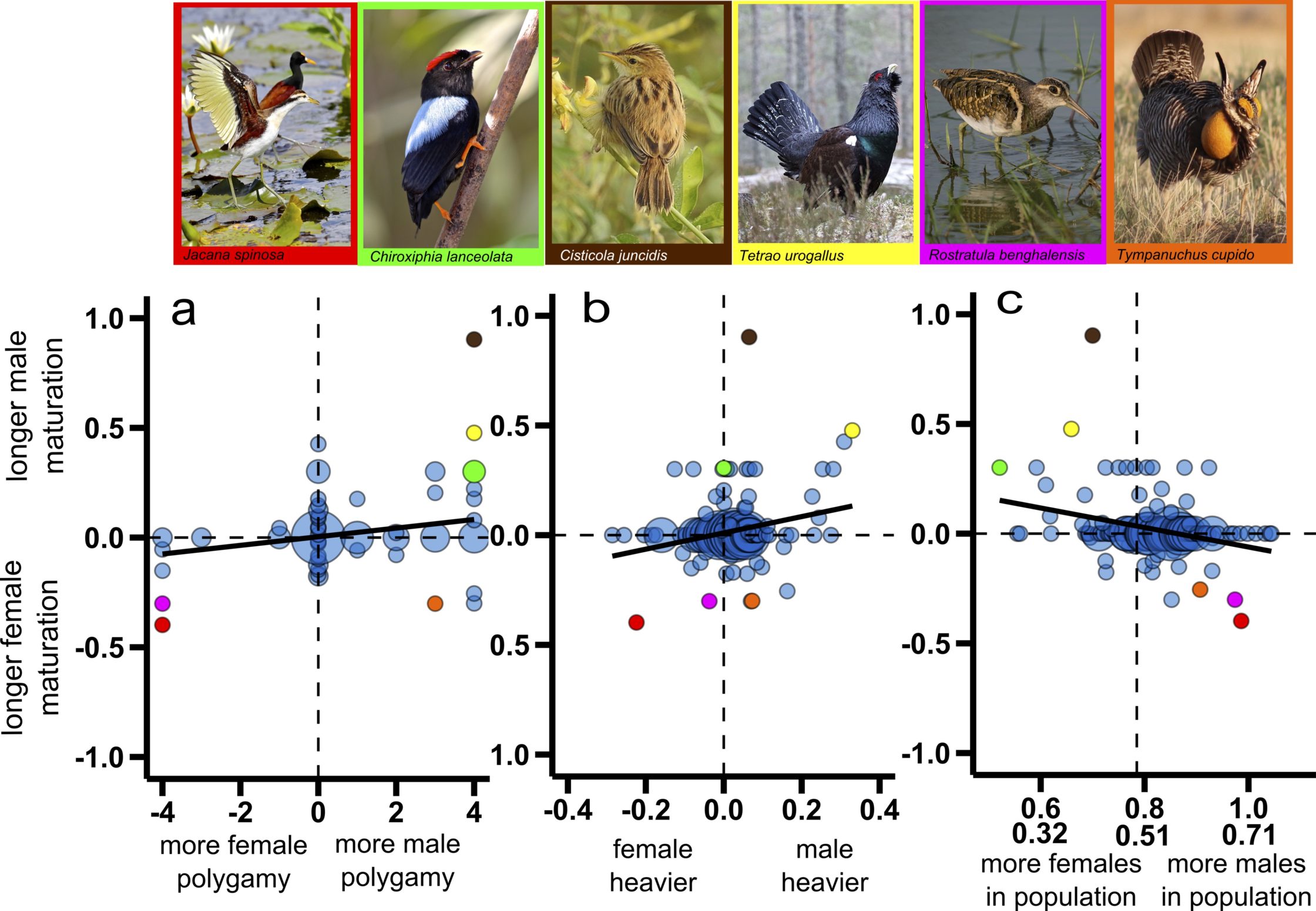

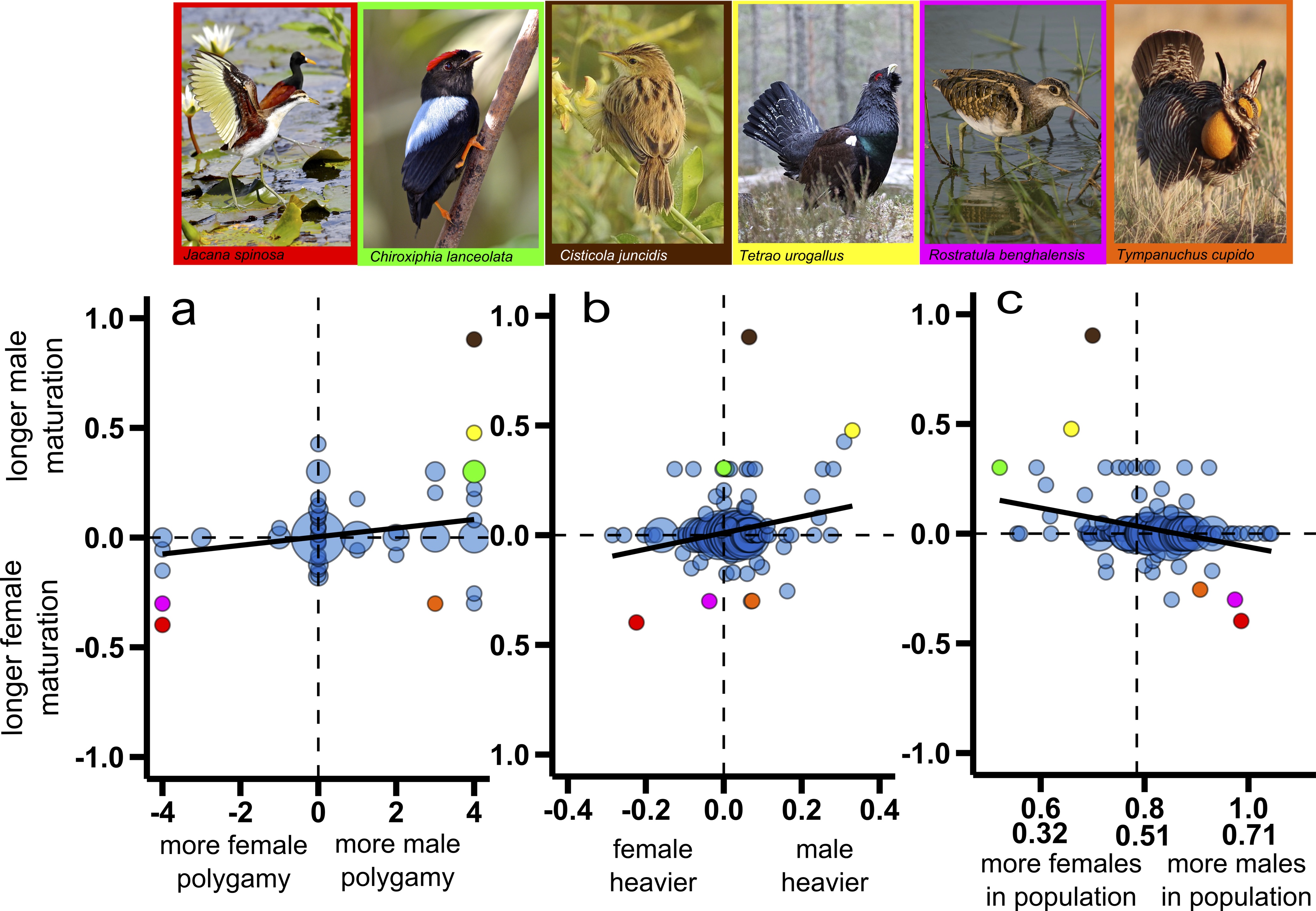

Using advanced phylogenetic comparative analyses and a comprehensive dataset that includes published information on age of sexual maturation, body size and sexual competition for males and females, as well as data on adult sex ratio for wild bird populations of 201 bird species from 59 families, we show that the sex that is larger, more promiscuous and rarer matures later than the sex that is smaller, less promiscuous and more abundant. Further exploration of likely causal connections between sex differences in age-to-maturation, two indicators of the strength of sexual selection (the extent of sexual size dimorphism estimated as sex differences in adult body mass and sex differences in the level of promiscuity) and the adult sex ratio suggests that female-skewed adult sex ratios drive the evolution of male-skewed sexual size dimorphism and male polygamy, which in turn promote the evolution of delayed maturation in males relative to females. Conversely, male-skewed adult sex ratios promote the evolution of female-skewed sexual size dimorphism and female polygamy, and these conditions favour evolution of delayed maturation in females relative to males. Thus, we conclude that the adult sex ratio, a proxy of the social environment, drives sexual competition, which in turn influences maturation. These exciting results highlight the significance of both sexual selection and social environment for sex differences in age-to-maturation, and contribute more broadly to our understanding of the evolutionary forces that generate sexual dimorphism.

Dr Sergio Ancona is a Research Associate at the Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). The original article is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.