A study published in Evolution Letters shows that hummingbird pollination is a surprisingly rare trait across the perennial wildflower genus Penstemon, despite a large number of Penstemon lineages having switched during their evolutionary history to attract hummingbird pollinators instead of bees. Here, the study’s author Dr Carolyn Wessinger tells us more about her findings.

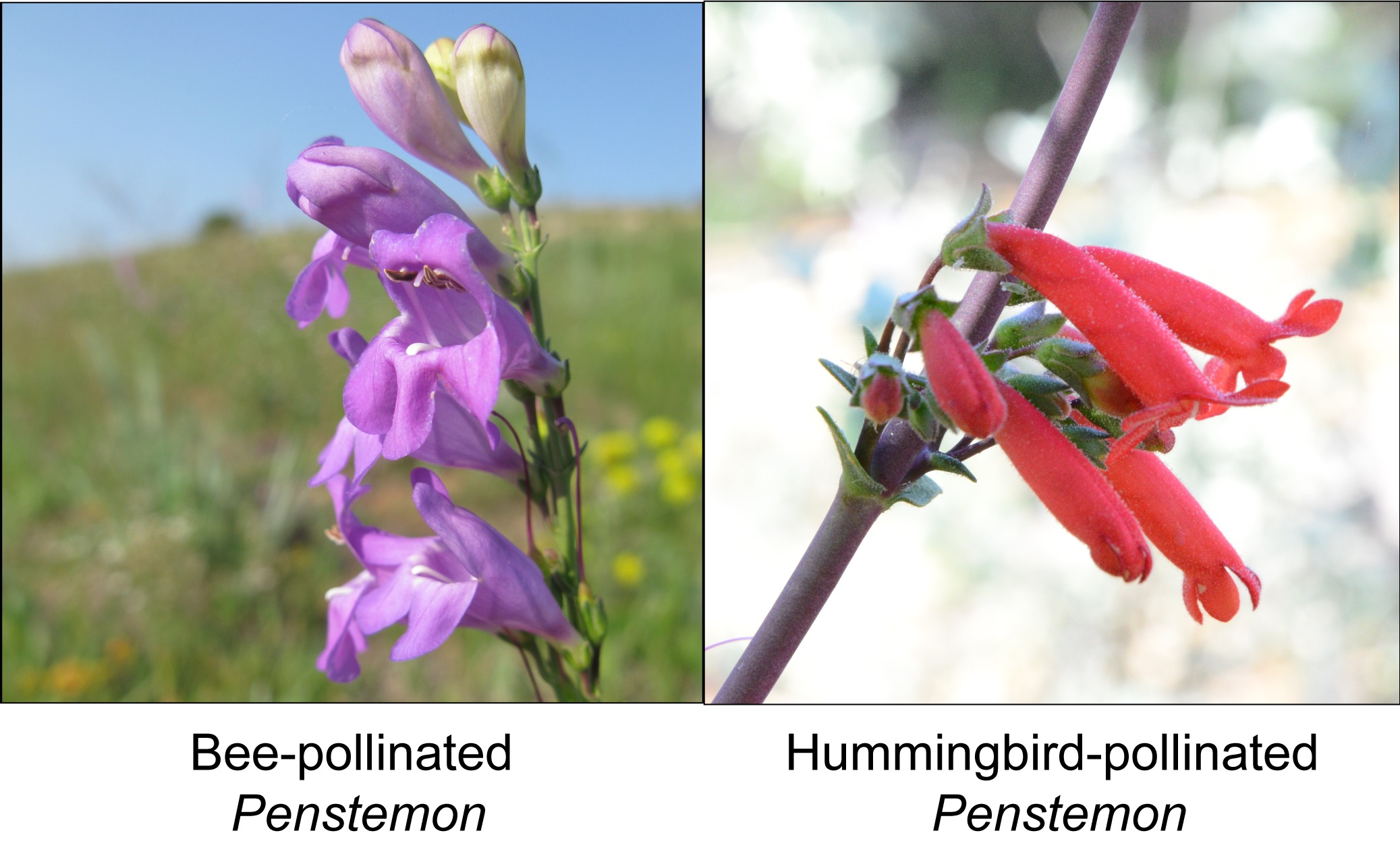

Many species of flowering plants have evolved flowers that attract a certain type of animal pollinator. For example, species that attract moth pollinators have white flowers that emit a strong and sweet floral scent, species that attract bees have blue/purple or yellow open flowers, and species that attract hummingbirds have bright red tubular flowers with lots of nectar.

Over evolutionary time – thousands to millions of years – a species might abandon its current pollinator and begin to attract a new pollinator, if it is profitable to do so. (Perhaps the old pollinator has become a less abundant or reliable pollinator). This should be beneficial in the short term, but it turns out there can be unexpected long-term consequences of switching pollinators!

In our new paper published in Evolution Letters, we study the effects of switching pollinators on plant species persistence and diversification using the perennial wildflower genus Penstemon. Most of the nearly 300 Penstemon species in North America are pollinated by bees or wasps – certainly has been a successful partnership in the long term. But roughly 15–20 lineages within Penstemon have switched to attract hummingbird pollinators instead of bees. Most likely, these species live in places where hummingbirds are locally abundant or efficient pollinators, making this a good short-term decision.

Because Penstemon has ditched bees for hummingbirds so many times, it is an ideal group of plants to examine the long-term consequences of switching to hummingbird pollination in North America. In a sense, nature has provided us with a large number of “replicated experiments” for us to study.

In our study, we reconstructed species relationships for a large branch of the Penstemon family tree, allowing us to trace the evolutionary history of transitions from bee to hummingbird pollination. Each origin of hummingbird pollination usually consists of just one or (rarely) two hummingbird-pollinated species, never leading to a large group of related hummingbird-pollinated species. This makes hummingbird pollination a surprisingly rare trait across the sampled Penstemon species, given the large number of times this pollination switch has occurred (17 switches to hummingbird pollination in our sample!).

What explains this rarity of hummingbird-pollinated species in Penstemon? Perhaps switches to hummingbirds occurred so recently that there just hasn’t been enough time for hummingbird-pollinated species to become more common. Another possibility is that there is a side effect of the hummingbird strategy that limits species diversification.

To examine these possibilities, we modeled speciation and extinction rates of each pollination strategies in Penstemon. We found that the net diversification rate (speciation minus extinction) for hummingbird-pollinated species is much lower, compared to the diversification rate for bee-pollinated species. So, a low diversification rate is apparently a side effect of hummingbird pollination in Penstemon.

Next we calculated how the relative numbers of bee- vs. hummingbird-pollinated species are expected to change over time, given the diversification rate difference that we have detected. We wanted to know: would this lower diversification rate be enough to keep hummingbird-pollinated species rare in the long term? The answer was yes: we expect hummingbird-pollinated species to be rarer than bee-pollinated species in Penstemon over the long term. So, it seems that switching to hummingbird pollination may be a great short-term strategy, but has an unexpected consequence of reducing diversification rates, relative to the bee pollination strategy.

A major unanswered question is why the hummingbird strategy leads to low diversification rates. Our study was not equipped to answer this question, but there are several possibilities. I’ll describe one of our favorites here:

A key feature of speciation is isolation. When a local population is isolated from other populations, it may begin to diverge and, given enough time, accumulate enough genetic differences that it constitutes a separate species. Perhaps hummingbirds move pollen great distances, at least occasionally, in the course of their seasonal migrations. Such long-distance pollination could help maintain genetic connections between geographically distant populations, hindering the speciation process. That’s not to say that hummingbird-pollinated species in Penstemon aren’t successful, since there are several species with very large range sizes in North America.

There is a lot to learn in the future about whether pollination strategy in Penstemon affects the organization of genetic variation within and between populations. This is where we are moving next with this research, so please stay tuned!

Dr Carolyn Wessinger is a postdoctoral fellow in the Hileman Lab at the University of Kansas. The original article is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.