A new study published in Evolution Letters demonstrates that males incur greater costs from investing in pre-copulatory reproductive traits, like courtship behaviour, than in post-copulatory traits, like sperm production. Lead author Meng-Han Chung tells us more.

“Why do animals age?” is a long-standing question in life-history, and theories suggest that it is about energy allocation. With limited energy reserves, each animal should optimally devote their resources into different fitness components, such as growth and immune response. However, in order to maximize reproductive success across their finite lifespans, animals heavily invest into reproduction, resulting in the damage of somatic functions over time and eventually influencing survivorship. Indeed, when animals in wild populations mature early and start to breed, they often have a shorter lifespan and/or poorer body condition at later adult age. Such evidence seems to support the pronounced costs of reproduction on senescence. However, more than eighty percent of these studies were based on data taken from females. This is partly due to the difficulty of measuring male reproductive traits in the wild. Therefore, we still don’t know much about the costs of male mating, in particular the components of male reproduction that contribute to the decline in later performance.

In order to reproduce a male has to first acquire a mate. This will involve mate searching, and potentially behaviors such as courtship displays. Having acquired a female, he then goes through the process of copulation, sperm release and subsequent sperm replenishment. Investments before copulation (mating behavior) and after copulation (sperm traits) have, to now, been treated as energy-consuming traits, but whether one is more costly than the other remains unaddressed. This is because ejaculation is always performed after mating behavior has been completed, making it very difficult to disentangle the two. If you think about it, it is nearly impossible to let a male interact/mate with a female while at the same time preventing him from ejaculating. But this is what is required experimentally in order to be able to quantify the relative costs of the two components of male reproductive investment. The logistical difficulty of separating mating and ejaculation has meant that we don’t yet have a good understanding of the relative ‘price’ males pay for mating versus sperm production.

Our study tackled this question using a unique feature of the mosquitofish, Gambusia holbrooki. Male mosquitofish adopt a coercive mating strategy, incessantly harassing females and attempting to mate. When the male finally gets close to a female, he inserts the tip of his intromittent organ (called the gonopodium) into her genital tract and expels sperm. We had found out that by removing the tip of the gonopodium, we could prevent mosquitofish males from releasing sperm. Furthermore, these males with their gonopodium tip removed continue to behave in exactly the same way as “intact” males: they continued to make as many mating attempts with the female, and were equally attractive to the female. Thus, the ablation didn’t affect any aspect of their courtship behaviours. This meant we could go on to try to tease apart the relative costs of mating and releasing sperm for male mosquitofish. In our experiment we had three types of males: (1) ‘naïve’ males who were kept in a tank with females, but not allowed mating contact and so didn’t have the opportunity to invest in mating or sperm replenishment; (2) ‘mating only’ ablated males that were housed with a female and could mate with her, but couldn’t ejaculate and so incurred the costs of mating but didn’t incur any of ejaculation costs; (3) ‘mating and ejaculation’ males who could freely interact with a female and also release ejaculates and so incurred the costs associated with mating behaviours and sperm release. Males were kept in the treatments for eight weeks, equal to the half of the breeding season for our Gambusia population in Canberra, Australia. By comparing these three groups, we were able to clarify the independent effects of mating and ejaculation.

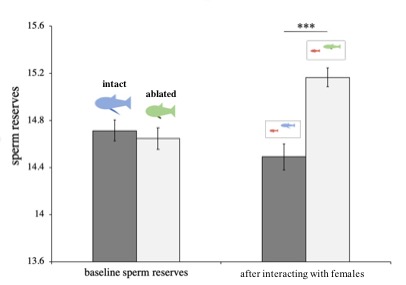

Left: The tip of male gonopodium. Male mosquitofish employ a coercive mating strategy: chasing the female and attempting to insert his gonopodium tip into the female’s gonopore in order to release sperm. Right: Ablated males cannot release sperm despite being in mating contact with a female. This is shown by the fact that sperm reserves of ablated males increased over the period spent in mating contact with the female, compared to intact males whose sperm reserves actually decreased.

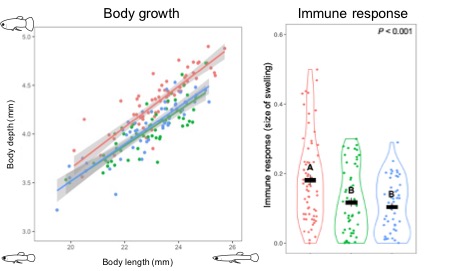

We found that the naïve males had faster adult growth and stronger immune response than males who had invested in mating. However, there was no difference in growth and immune function between ‘mating only’ and ‘mating and ejaculation’ males, suggesting that resources invested into mating behaviours are where males pay the price in terms of somatic functions, rather than in terms of the extra costs of sperm replenishment.

Differences in growth and immune response between ‘naïve (red)’, ‘mating only (green)’ and ‘mating and ejaculation (blue)’ males. Letters show different levels of immune response between treatments.

When examining male reproductive performance after the eight-week treatment period, we found trade-offs between current and future reproductive performance but only within the same traits. That is, males who had invested in mating behaviours displayed lower numbers of mating attempts compared to naïve males; and males who previously invested in both mating and ejaculation produced lower quantities of sperm within their ejaculates than both naïve and ‘mating only’ males. Interestingly, the impact of continuous investment in ejaculation on future sperm production was only found within smaller males, while the effect of mating effort on future copulatory performance was found across males of all body sizes. Why the significant impact of previous investment in sperm production on later-life sperm count is size-dependent remains unclear. However, it is possible that smaller males have lower energy storage capacity, meaning that the costs of sperm replenishment have a disproportionately higher impact.

In sum, if you are a male mosquitofish and hoping that a female gets pregnant with your babies, remember that mating behaviour is more costly than sperm release. Effort that males put into mate acquisition led to a reduction in growth, immune function and future ability to mate; but costs of ejaculation was only evident for smaller males in terms of their rate of sperm production. Our experiment therefore starts to unpack some of the traditional assumptions about fecundity and longevity trade-offs – this time from the male perspective.

Meng-Han Chung is a PhD student in the Jennions Group at the Australian National University. The original article is free to read and download from Evolution Letters.