A new study published in Evolution Letters shows that species with different sex chromosomes can interbreed. Lead author Prof Christophe Dufresnes tells us more.

How do organisms become male or female? It varies between vertebrates. Humans, like all mammals, do it with a Y chromosome – a chromosome that carries a “male determining” gene that is therefore only ever found in males. When it is the male that carries this “sex-limited” chromosome, it is termed an XY system: males are XY and generate daughters and sons by transmitting the X or the Y, respectively, while females are always XX. Another system exists, however, in which a gene determines femaleness. The chromosome holding that gene is called the W. In these “ZW” systems, the females carry Z and W, and transmit either one to the next generation to make ZW females or ZZ males.

Mammals and birds are known to have extremely old sex determining systems (hundreds of million years old). But the situation in amphibians (frogs, toads, salamanders) is much more dynamic. Closely related lineages (some less than 2 million years diverged) can possess different sex chromosome systems – either XY or ZW, and not necessarily involving the same chromosome pairs. Some frogs even use several chromosome pairs at the same time. In fact, sex-determination mechanisms have switched so many times that it is hard to keep track of their evolution, and since only a few mutations may suffice to trigger male vs female development, this makes sex chromosomes challenging to study. Needless to say, the amphibian tree of life is a mosaic of sex determining systems, and this means that these systems can sometimes collide. This is what happened between two widespread European amphibians, the common toad Bufo bufoand its sister species the spiny toad Bufo spinosus.

This spiny toad (Bufo spinosus), like us humans, determines sex with XY chromosomes, but its closest relative (Bufo bufo) uses a different system (ZW). Despite this, they can still hybridize, but most foreign genes do not make it very far.

Based on appearance alone you would be forgiven for thinking that B. bufo and B. spinosus were the same species. In fact, they were not officially recognized as different species until 2012. After the last ice age, they expanded from separate refugia in southern (B. spinosus) and eastern Europe (B. bufo), and now meet all over France at so called “secondary contact zones”. These sites are goldmines for scientific studies, as they act as natural experiments to learn what happens when diverging lineages hybridize. Do they merge back into one species, or have they become so different that their genomes have accumulated incompatibilities?

It was as part of a global effort to address these fundamental questions using next-generation sequencing in Eurasian amphibians that I initially focused on the B. bufo / spinosus contact zone with Dr. Pierre-André Crochet (CNRS), and we started collecting samples with local naturalist societies. But this contact zone came with a surprise. Our preliminary analyses revealed XY genetic markers in some southern samples, assigned to B. spinosus, while toads from the genus Bufo had been believed to be ZW since the 1940s! This is exactly the sort of genome incompatibility that would hamper hybridization and facilitate the divergence of new species. So, this result warranted more exploration!

We subsequently sampled dozens more samples including adults and a few families (parents and tadpoles) from each species, in collaboration with Dr. Daniel Jeffries (University of Lausanne), who specifically developed a new statistical method to analyze sex chromosomes using our large genomic datasets. These efforts corroborated that B. bufoand B. spinosus had distinct ZW and XY sex chromosomes, a striking example of how labile sex-determination can be in amphibians. On this topic, we published another study detailing switches between XY to ZW systems in Eurasian tree frogs, together with colleagues from Riverside, Harvard and Lausanne.

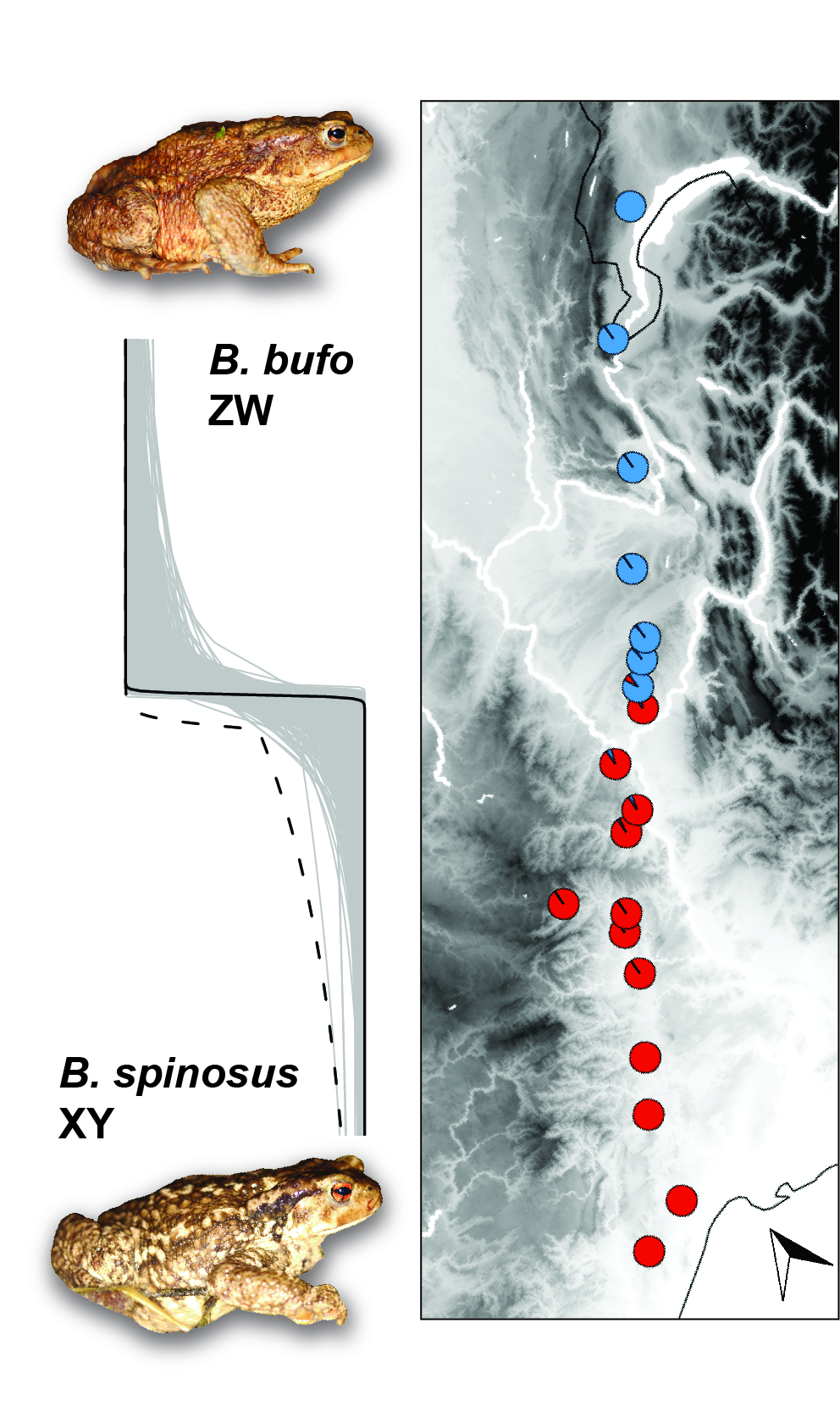

Our sampling transect along the hybrid zone between Bufo bufo (blue) and Bufo spinosus (red) in southern France. On the map, notice how the transition switches from B. bufo to B. spinosus within a few short kilometers (blue-red contact).

The left graph details the transition for hundreds of genetic markers separately. Notice how much smoother the transition is on the B. spinosus side for a few genes, as B. bufo variants reached far south (e. g. the dash line). This is potentially a sign that B. bufo was replaced in the south, but some of its genes still persist.

We knew by then that these closely related species were in close contact with each other, but had different sex determining systems, one XY and one ZW. So the big question was, what happens when they attempt to reproduce with each other? Using thousands of genetic markers, we confirmed gene exchanges between the species, indicative of hybridization. This is already an important result – they are able to reproduce. However, the genomes showed very restricted patterns of mixing, with no hybrids found more than few kilometers outside the contact zone. This suggests that hybrids probably suffer from reduced survival and/or fertility.

Despite this, faint genetic traces of B. bufo were detected as far south as the Mediterranean coast, within the B. spinosus populations. These results appear to be conflicting at first glance, but by modelling ecological preferences, a collaboration with Dr. Spartak Litvinchuk (Russian Academy of Sciences), we think that this may be because the southern species B. spinosus, which seems better adapted to Mediterranean conditions, has been shifting northwards for hundreds of years, pushing B. bufo out of Provence – a phenomenon perhaps intensified by global warming.

We cannot firmly draw a causal link between the restricted admixture and the differing sex chromosome systems at this stage. Sex chromosomes are often involved in the problems experienced by hybrids, at least in mammals and birds, but this not necessarily true of amphibians, where sex chromosomes are so dynamic that they do not accumulate as many defects or sex specific functions. So, as always, there is more work to be done. Next on the list is to examine the sex and condition of hybrids from controlled crosses between the two species and to see if some of the inherited combinations of sex chromosomes (e. g. ZW–XY, ZZ–XX) are more viable than the others.

This strange toad case raises awareness about the potential role of sex-determination mechanisms on the formation and maintenance of novel species. This perspective will be fascinating to explore in additional amphibian groups that similarly feature evolutionary lability in sex determination.

Christophe Dufresnes is Professor at the College of Biology and the Environment, Nanjing Forestry University. The original article is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.