In a new paper published in Evolution Letters, a research team from Tohoku University reveal the evolution of a gene related to human-unique psychiatric traits. Here, authors Daiki Sato and Masakado Kawata tell us more about their findings.

How and why unique human characteristics, such as highly social behavior, languages, and complex cultures, have evolved is a long-standing question. In our laboratory, we have focused on problems as to what factors facilitate and/or constrain evolution using mainly non-human organisms. However, during recent years, a large amount of genomic data, especially for human genome, have been accumulated, and thus, we can now attempt to resolve the mechanisms underlying human evolution using various methods to detect the signature of various forms of natural selection in the human genome.

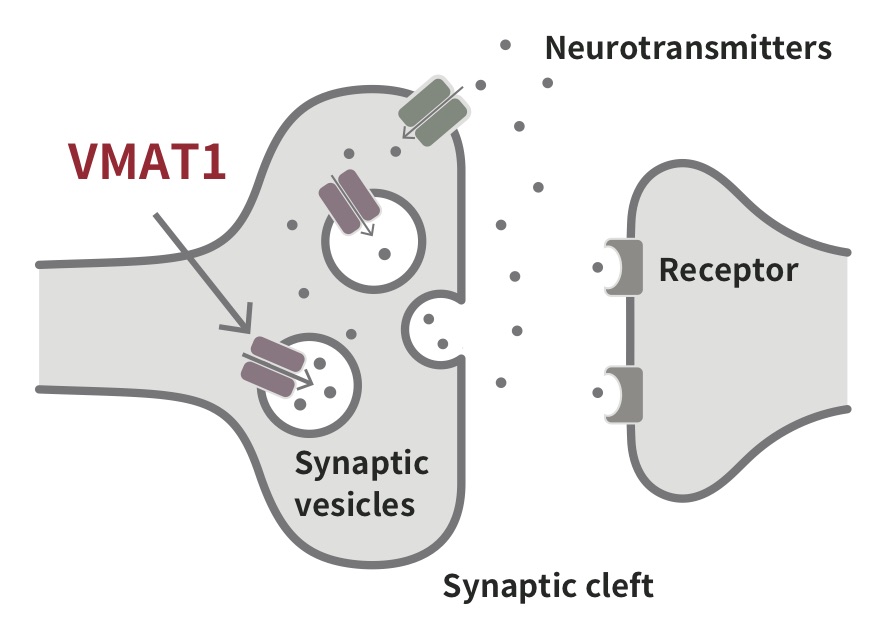

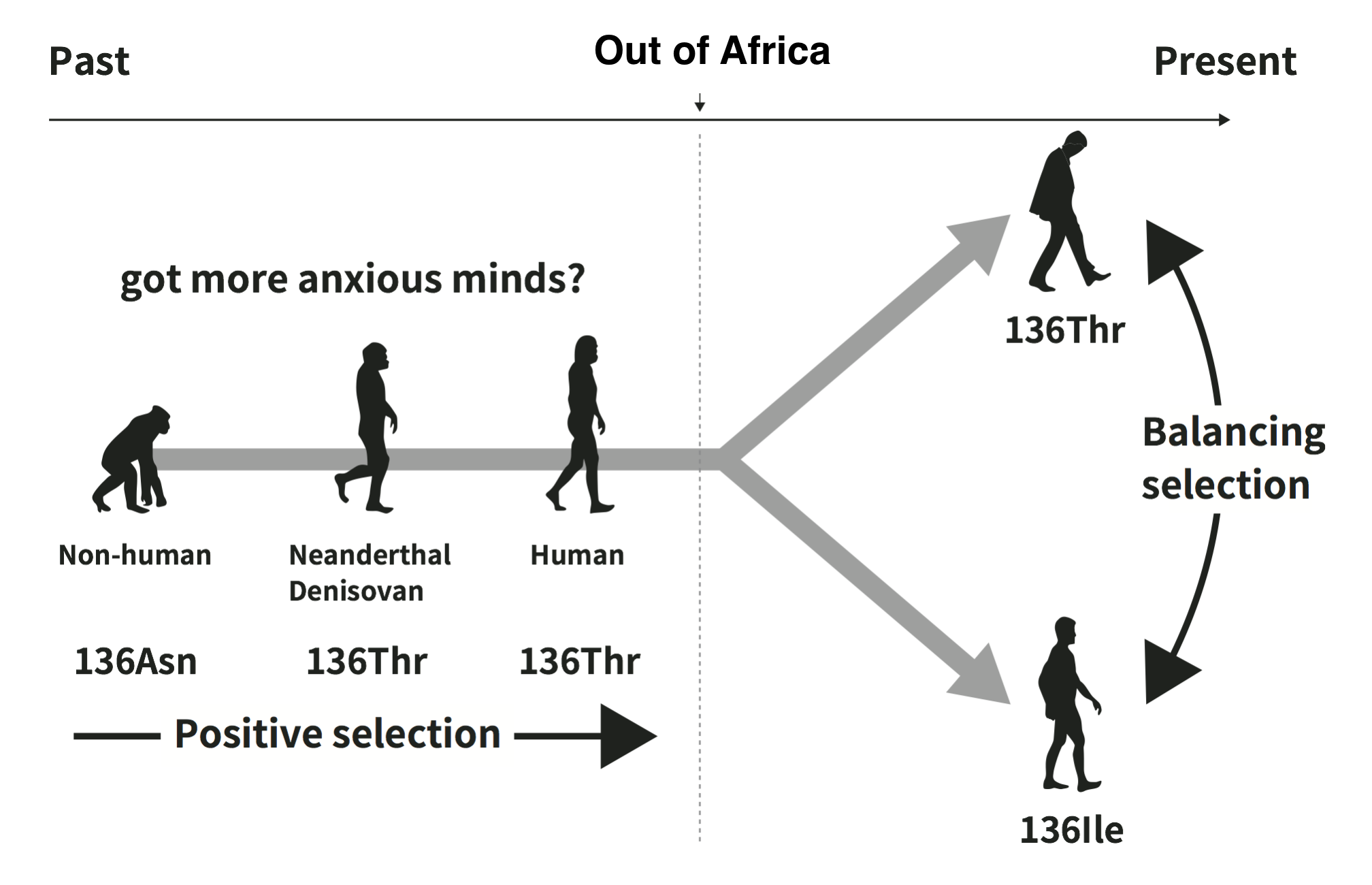

The first motivation for our study came from the hypothesis that some psychiatric disorders (PDs) have evolved as maladaptive byproducts of adaptive human evolution. In addition, recent studies have shown significant genetic correlations between PDs and human personality traits, such as neuroticism, extroversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, posing the question of how adaptive evolution has shaped our psychiatric and/or personality traits. Thus, among PD-related genes, we searched for those that have been favored by natural selection in the human lineage and identified three as positively evolved genes associated with some PDs, although several studies using the same approach could not identify these genes. Of the three genes identified, we focused on SLC18A1 because it has interesting known variants that affect PDs. SLC18A1 encodes vesicular monoamine transporter 1 (VMAT1), which is involved in the uptake of monoamine neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, into synaptic vesicles. VMAT1 has variants of two different amino acids, threonine (Thr) and isoleucine (Ile), at site 136 (Thr136Ile). Several studies have shown that these variants are associated with PDs, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and neuroticism. Individuals with 136Thr tend to be more anxious, more depressed and have higher neuroticism scores. Our paper showed that other mammals have 136Asn at this site, but 136Thr had been favored over 136Asn during human evolution. Moreover, 136Ile variant had originated nearly at the Out-of-Africa migration, and then both 136Thr and 136Ile variants were maintained by natural selection in non-African populations.

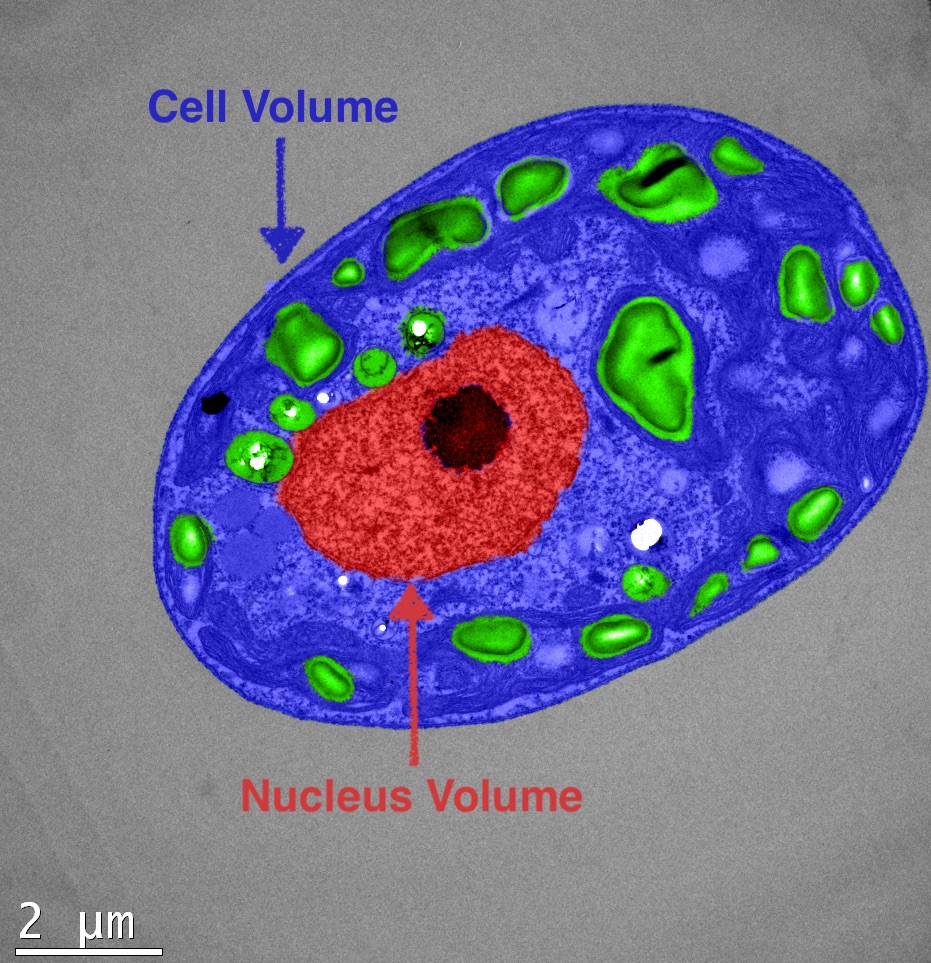

is involved in transfer monoamises, such as dopamine and serotonin. Image by Daiki Sato

Our results provide two important implications for human psychiatric evolution. First, through positive selection, the evolution from Asn to Thr at site 136 on SLC18A1 might have led to more anxious and depressed human minds in the course of evolution from ancestral primates to humans. Inoue-Maruyama et al. (2001) speculated from an analysis of serotonin-transporter variants that anxiety has been favored throughout human evolution. Raghanti et al. (2018) proposed a neurochemical hypothesis that selection favored a human dopamine–dominated striatum (DDS) personality style in our earliest ancestors, which led to externally driven behavior and amplified sensitivity to social cues that promote conformity, empathy, and altruism. The results of their study showed that the concentration of dopamine in the striatum was particularly elevated in humans, and that acetylcholine was lowered. The 136Thr variant might be favored for interacting with such complex neurochemical changes during the evolution of human psychiatric and emotional features.

Second, we showed that the two variants of Thr136Ile have been maintained by natural selection using several different methods. Any form of natural selection that maintains genetic diversity within populations is called “balancing selection”. Thus, our results suggest that some components of personality traits in human populations that are affected by genetic variants are maintained by balancing selection. Individual differences in personality traits are observed in various human populations, and some of these personality traits are also found in non-human primates. This suggests that genes associated with personality traits could generally be maintained by balancing selection, although there is no clear evidence for this process in human neurotransmitter genes (Taub and Page, 2016). Balancing selection can be caused by several factors, such as heterozygote advantage, negative frequency–dependent selection, environment–genotype interactions, and intralocus sexual conflict. Detecting balancing selection from genome sequences is often difficult because balancing selection often does not continue over long periods of time and might be transient. In particular, phenotypic and fitness effects of PD-related genes are expected to change depending on the environments and their surrounding social interactions. These complex interactions sometimes cause emergent overdominance (heterozygote advantage emerges by averaging over different populations, environments, or generations; Delph and Kelly, 2014). In these cases, the strength and effects of balancing selection can often be inconstant. In our study, balancing selection for Thr136Ile variants was detected in only several non-African populations; therefore, this process might depend on one’s physical and/or social environments. Taken together, we propose that genes associated with personality traits have actually been maintained by varying the process of balancing selection, but detecting this would be difficult using previous methods. We must now consider how to detect weak selective pressure in the evolution of diverse individuality and personality traits.

In our ongoing research, we are attempting to identify the phenotypic and fitness effects of Thr136Ile variants and clarify how and why the variants are maintained by balancing selection.

Daiki X. Sato is a PhD student and Masakado Kawata is Professor at the Graduate School of Life Sciences, Tohoku University. Their original study is freely available to read and download here.