Why do individuals vary in how quickly they age? Eve Cooper explains what her new research tells us about the effect of developmental environment on senescence.

As humans, the process of senescence – experiencing physiological declines as we age – is a seemingly inescapable constraint of our own biology. But why is it that we must senesce? Is senescence a resolute attribute of life on earth, or a malleable trait, with the ability to evolve – or even disappear altogether? These questions are at the root of deciphering the evolutionary origins of the ageing process.

Up until recent decades it was commonly assumed that wild animals rarely experienced senescence. The argument went that the risk of death from extrinsic conditions (such as predation, starvation, or exposure) was so high in the wild that animals rarely survived to reach the old ages necessary to experience senescence. Hence, senescence was a negligible phenomenon outside of modern human society. It has only been through the long-term collection of detailed individual-based data from wild animal populations that this assumption has been largely disproven. Senescence is observed to occur in the wild across a broad range of different species, and actually seems to be the norm, rather than the exception.

Another fascinating finding that resulted from these long-term wild animal studies is that there is often dramatic variation between individuals living within the same population in how fast or slow they senesce. This discovery begs a new and important question about the evolution of senescence. Assuming that slower senescence results in higher evolutionary fitness, we should expect natural selection to wean out those with faster senescence rates, and drive evolution towards slower, potentially even negligible senescence in the wild. However, the persistence of variability in senescence rates between individuals indicates that the evolution of senescence is being inhibited in the natural world. Understanding the mechanisms driving the persistence of senescence is essential in building an evolutionary framework through which we can understand ageing.

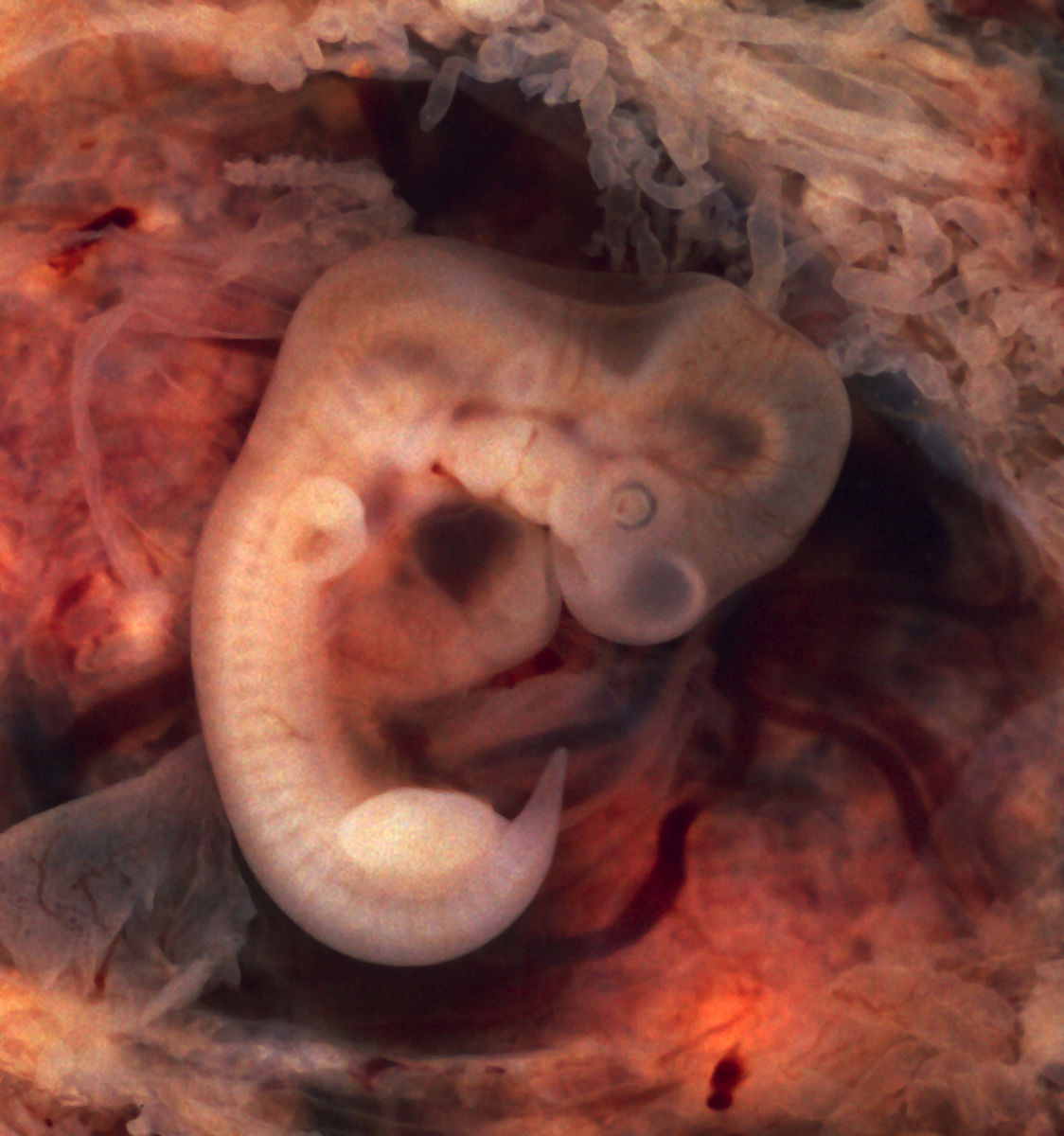

So what causes some individuals to decline faster than others? As with many things in ecology, the underlying mechanisms have proven to be complex. Genes are partially responsible in determining senescence rates – individuals may be genetically predisposed to decline slower or faster. Additionally, the environment plays a role – animals exposed to harsher conditions can generally be expected to senesce faster. It is well established that genes and the environment interact in influencing senescence rates. However, it may not be only the current environment that interacts with genes in affecting senescence rates. There is good evidence that the first stage of life, the developmental period, has crucial influence on many traits into adulthood. For example, in humans, poor nutrition and stress during pregnancy has been linked to higher rates of cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the adult life of the offspring. In other animal species, developmental environment has been linked to adult body condition, survival probability, and reproductive success. What if the environment experienced during the very first stage of life, the developmental period, has influence so profound that it resonates into the very last stage of life, influencing rates of senescence?

The goal of our research, published today in Evolution Letters, was to provide a quantitative synthesis of the effects of developmental environment on rates of senescence in wild animals. Using data from long-term studies of 14 different species in wild populations, we conducted meta-analyses to determine the effect of developmental environment on two different types of senescence rates – survival and reproductive senescence. The effect of developmental environment was quantified using measures of nutritional availability or stress experienced during gestation or as a juvenile, including attributes of food availability, population density and weather conditions.

We found that, although there is no association between developmental environment and survival senescence rates, there is a significant association between developmental environment and reproductive senescence rates. An individual born into a better environment is likely to experience slower rates of reproductive decline in late life. This indicates that a higher quality developmental environment can act as a proverbial “silver-spoon”, applying positive influence to the very end of life.

What do these results mean for our broader understanding of the evolution of senescence? The silver-spoon effect indicates that genes can interact with past environment to influence senescence. Since the influence of developmental environment on senescence is non-genetic, it has the potential to weaken the force of natural selection acting to slow senescence rates in the wild. Ultimately, this silver-spoon effect represents a mechanism that could potentially reduce the ability of senescence to evolve. This may help explain why we see dramatic variation in senescence rates between individuals, and why senescence is not evolving in the expected direction of slower rates and longer lifespans. A better understanding of senescence in an evolutionary framework has broad importance, not only to evolutionary biologists, but as a fundamental framework useful in all scientific efforts to combat the negative effects of senescence and improve well-being as we age.

Eve Cooper is a PhD student at The Australian National University. The original study is freely available to read and download here.