A new study published today in Evolution Letters shows that populations with an evolutionary history of strong sexual selection are able to invade competitor populations more rapidly. Here, lead author Dr Joanne Godwin tells us more.

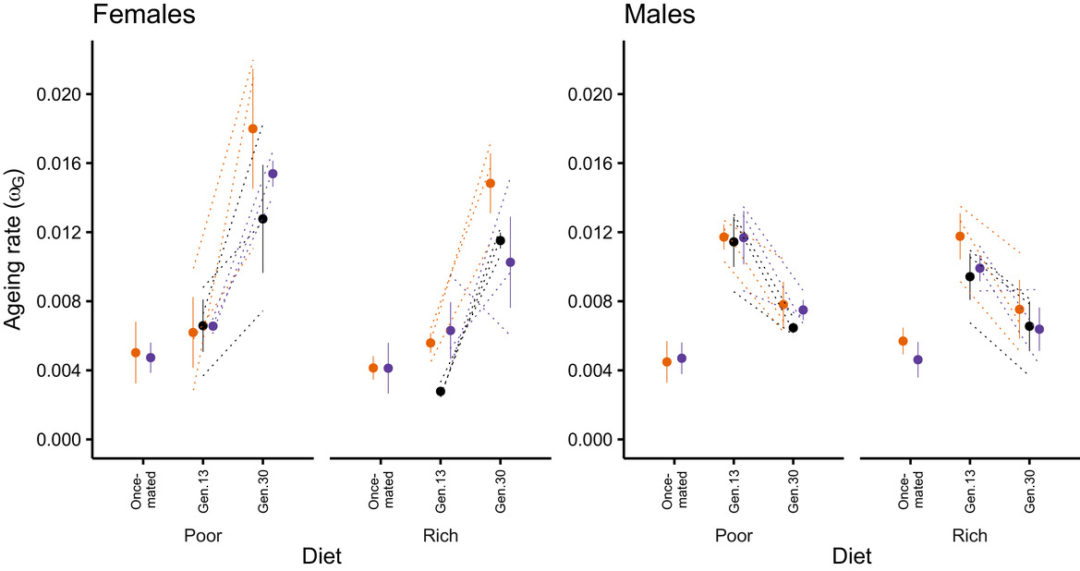

Costs: sexual selection vs. natural selection

No discussion of sexual selection is complete without the clichéd picture of a peacock. Peacocks even featured in Darwin’s original thinking on the mechanisms of evolution, causing him to write that ‘the sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick’, due to their apparent lack of survival value. Peacock feathers exemplify extravagant sex-specific traits which, although energetically costly and sometimes with negative impacts on survival, evolve due to the advantage they provide for mating and reproductive success.

Iconic sexually selected traits also include antlers and horns used in both competition between rivals and as a signal for mate choice. However, it has been suggested that the vast antlers of the Irish Elk may have been so costly that it pushed the species over an ‘extinction threshold’. The balance between investing in reproduction or survival is thus a delicate one and while we understand many of the costs and benefits of sexual selection for individuals, how this impacts at the population level remains unclear.

Benefits: heightened condition and reduced mutation load

While peacock feathers may have caused Darwin some disquiet, he also describes how ‘sexual selection will give its aid to ordinary selection, by assuring to the most vigorous and best adapted males the greatest number of offspring’, suggesting that, rather than working in opposition, these evolutionary forces could or should work alongside each other.

The elaborate and costly nature of many sexually selected traits means their development and maintenance is often dependent on the ‘condition’ of an individual – the pool of resources available to allocate to traits. The greater this pool of resources, the more can be allocated not only to brighter feathers or larger antlers, but also to development, growth, repair and fecundity. The greater an individual’s condition, therefore, the more likely they are to maximise their evolutionary fitness. Crucially, this means that any behavioural, physiological or biochemical trait which allows an individual to increase their pool of resources, or to make more efficient use of them, will be favoured by sexual selection as well as natural selection. Alignment of sexual and natural selection for improved condition can therefore create lineages and populations with increased average fitness.

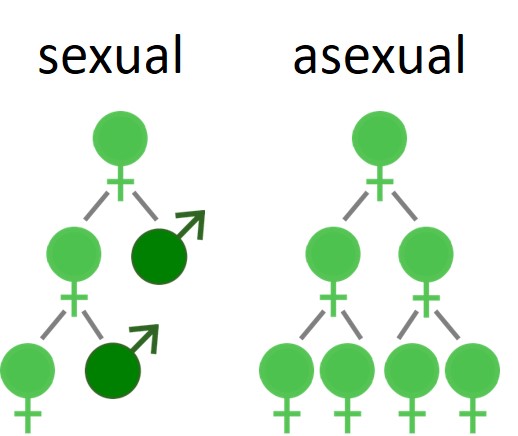

In addition, if sexual selection acting via competition between rivals and mate choice, ensures only those in highest condition gain the greatest share of reproductive success and contribute the most to the next generation, this should increase the rate that beneficial alleles become fixed and aid the removal of deleterious mutation load. Furthermore, the variety of traits which can improve condition means these processes could occur across the whole genome. Key papers by Agrawal (2001) and Siller (2001), suggest the longer-term benefits to populations of reduced mutation load across the genome, could outweigh the cost of producing males and explain the maintenance of sexual reproduction.

Invasion ability: a holistic test of fitness

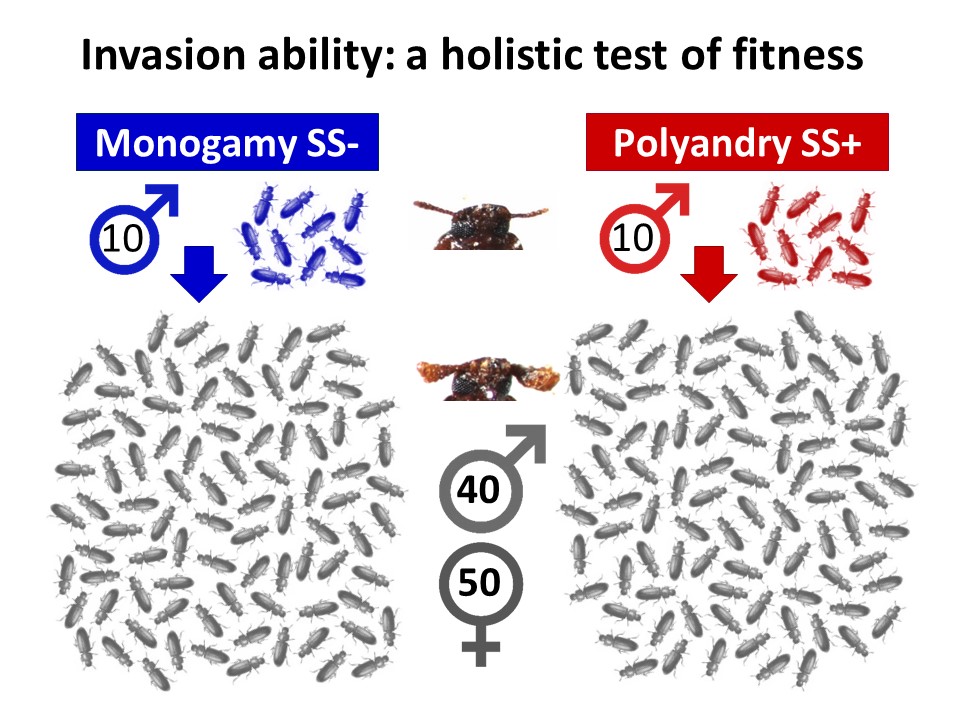

Our new study tested the idea that an evolutionary history of sexual selection can improve mean fitness within a population, compared to when it is removed. We used the ability of individuals from contrasting sexual selection backgrounds to invade into competitor populations across multiple generations as a holistic measure of overall fitness. Invasion success will depend on a wide range of traits in both sexes and a competitive advantage across life stages and generations, therefore incorporating key fitness components of viability, fecundity and haploid selection in addition to mating and fertilisation success.

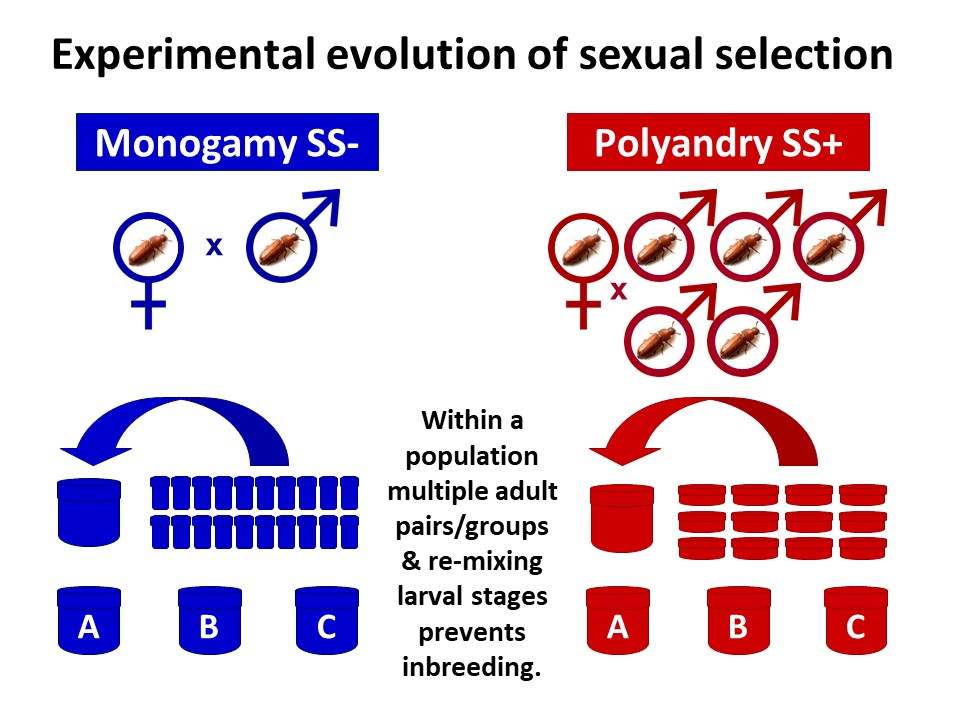

We made use of experimentally evolved populations of the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum, having experienced 77 generations of contrasting strengths of sexual selection under either monogamous or polyandrous mating systems during the adult life stage. Within these populations and at every generation, adults are placed in either polyandrous groups (1 female and 5 males) creating opportunities for competition between rivals and choice of mates (SS+), or monogamous pairs (1 female and 1 male) which removes competition and choice (SS-).

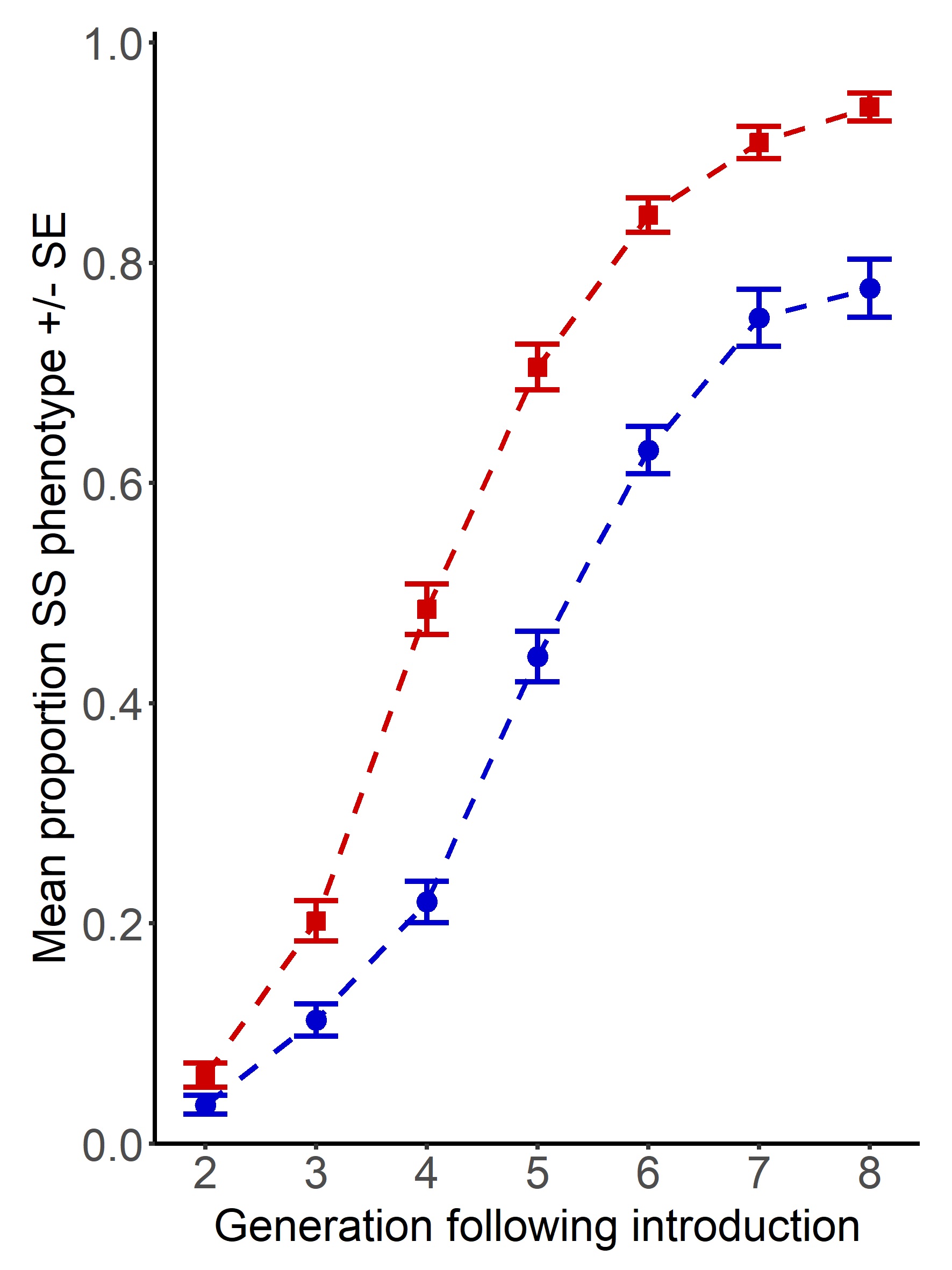

Males from these sexual selection backgrounds were introduced into small populations of a novel competitor strain, known as ‘Reindeer’ due to their distinctive swollen antennae, which allowed us to monitor the spread of the wild-type phenotype displayed by the invaders. Having colonised the larger Reindeer competitor populations with a handful of males from strong or weak sexual selection backgrounds, we tracked invasion across the following 8 generations, measuring any genetic spread linked to the marker phenotypes.

Our results show that where individuals have an evolutionary history of polyandry (red), they are able to invade more rapidly and completely than those with a history of monogamy (blue). At the end of the year-long invasion experiment, invaders from higher sexual selection backgrounds had almost completely eliminated the original competitor population background. To understand what particular advantages are gained under stronger sexual selection, we followed this up with assays of fertility and population genetic simulations which suggested that fitness is improved through the offspring, as well as adult life stages, in both sexes.

Why does this matter?

Evidence that sexual selection improves average population fitness provides empirical support for models explaining how costly sexual reproduction can persist. Moreover, populations are facing ever-increasing threats from habitat loss and fragmentation, overexploitation and environmental change. So, in addition to the alignment of natural and sexual selection being an interesting theoretical question, it will also have important implications for population viability, extinction risk and conservation planning.

Dr Joanne Godwin is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of East Anglia. The original study is freely available to read and download here.