How do organisms protect themselves against harmful parasites? One way might be to form mutualistic relationships with microbes who help defend their host. A new study, published in Evolution Letters, has demonstrated that beneficial co-dependent relationships can evolve remarkably quickly between hosts and bacteria, with important positive effects on host health. Luke Turner reports:

Organisms interact with each other in a variety of ways, and relationships that form between the individuals of different species fall somewhere along a gradient known as the parasitism-mutualism continuum. This scale indicates how beneficial the organisms are to each other, with “mutualism” describing cases where individuals provide reciprocal benefits, while “parasitism” occurs when one organism profits at the expense of the other. These associations are formed through long term co-evolutionary interactions, but their position on the continuum is dynamic and can shift over time if the nature of the relationship changes.

When parasites exploit other organisms they must attempt to evade the defences of the host, which evolve in order to protect them from this costly infection. One way in which hosts can defend themselves from parasites is through the actions of organisms that live within them. These microbial symbionts can offer inadvertent protection against virulent parasites, with hosts in turn giving the defensive microbes a place to survive, therefore forming a defensive mutualism. This relationship straddles the parasitism-mutualism continuum, as defensive microbes are costly for their hosts to sustain in the absence of a virulent parasite. Therefore for the host, this defensive mutualism is only worth investing in when they are susceptible to the infection of a virulent parasite, and when the microbial symbiont can offer effective protection.

Defensive mutualisms are widespread and have been identified across a number of plant and animal species, including in humans. These mutualistic host-microbe relationships are thought to be the product of long term co-evolutionary interactions, however little is known about how or why they are initiated. The answer to their adaptive origin may lie with the fact that hosts are normally infected with a number of different parasite species simultaneously. This coinfection often leads to one parasite species reducing the effectiveness of a competing species, which indirectly benefits the host by providing protection. As long as the protecting parasite is only mildly virulent, and it is preventing a more virulent parasite from infecting the host, this forms the basis for co-evolution between a host and the microbial symbiont.

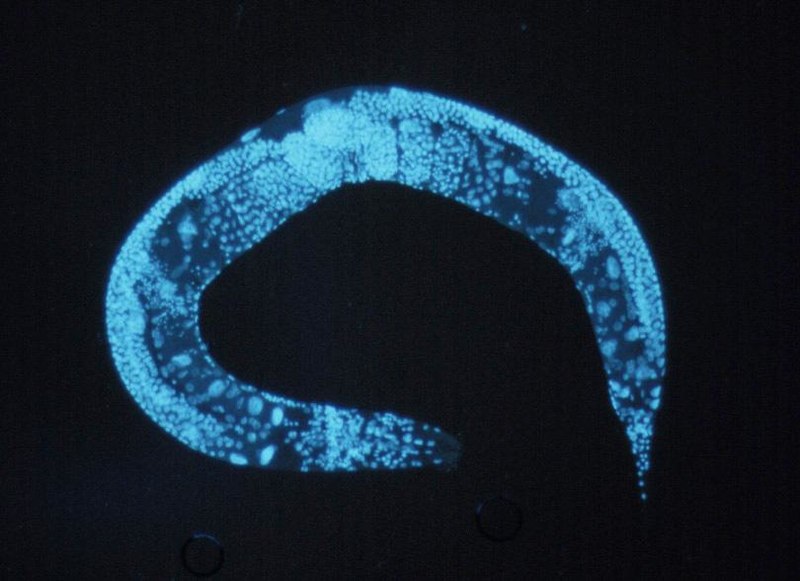

New research carried out by Rafaluck-Mohr et al. (2018), published in Evolution Letters, set out to investigate the conditions under which these defensive mutualisms emerge. Using an experimental approach, they infected a host, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, with Enterococcus faecalis, a costly bacterium that had previously been found to defend the nematode against a different, more virulent parasite (Staphylococcus aureus). Hosts were then exposed to the more virulent parasite, and the study found that when nematodes were subjected to coinfection by both types of parasite, E. faecalis evolved to protect them against the more virulent strain. Consequently, the defending bacteria colonised the nematode hosts at a greater rate.

These results indicate that the nematode hosts evolved reduced resistance to E. faecalis, due to the simultaneous benefits of the relationship between host and defensive microbe. With the help of a mathematical model, the study simulated the scenario in which two parasites infect a host. This model shows that when one parasite provides at least an intermediate level of protection to the host against a more virulent parasite, a defensive mutualism can form between host and microbe. Furthermore, the study demonstrates that ongoing host-parasite interactions are dynamic, and can readily transition to mutually beneficial relationships if there is a shared enemy in the community (in this case, the more virulent parasite).

One of the most exciting findings of this research was the speed with which the mutualistic relationships formed. From the time the nematode hosts were first exposed to the parasites, it took a maximum of 14 host generations for E. faecalis to provide heightened protection against the more virulent S. aureus. In coevolutionary terms this represents a rapid timeframe for this type of interaction to arise. Furthermore, these beneficial defensive bacteria are transmitted between different hosts horizontally, meaning that they can pass between individuals of the same generation in real time. These are exciting findings as they show that there is specific co-adaptation taking place between the host and the mutualistic parasite.

As one of the first experimental demonstrations of hosts increasing their susceptibility to the defensive symbiont E. faecalis, this study shows that hosts can select for microbial colonisation as a defence against other parasites. Despite infection of the symbiont remaining costly to the host, it is worthwhile investing in this symbiotic relationship when they can provide at least an intermediate level of protection. The fact that these associations can form so quickly is encouraging for the fight against deadly human parasites such as Zika, as microbial partners have the potential to provide human hosts with protection against their transmission.

Luke Turner is a MSc Science Communication student at the University of Sheffield. The original study is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters here.