Invited author blog by Rees Kassen

It will come as no surprise to most readers of this blog that antimicrobial resistance, or AMR for short, is a major global health challenge. Every year since 2013 there have been global warnings – from the World Economic Forum, the World Health Organization, and the United Nations General Assembly – that the world is at risk of entering a post-antibiotic era. When the drugs don’t work we get sicker more often and stay sicker longer. Something has to be done.

Ideally, we would reduce the global burden of AMR by decreasing the quantity of drugs we use. The logic here is straightforward. The widespread use of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture means that drug resistant types enjoy a strong selective advantage and can quickly spread. So, by reducing the use of drugs we reduce the selection pressure on resistance and slow the rate at which AMR evolves and spreads. Simple.

Except it’s not. How, precisely, should we reduce the volume of drugs we use? We can’t just introduce a blanket ban on prescriptions and stop using drugs altogether. If my loved one is sick and there is a drug that can make them better, I want that drug. But maybe we could deliver our drugs in ways that would make it harder for resistance to evolve and spread, and so prolong the amount of time a drug remains effective? This was the question that launched our research.

One suggestion is to make use of drug sanctuaries – drug-free environments – to effectively reduce the strength of selection for resistance. If drug sensitive types have a growth advantage over resistant types when no drug is around, then sensitive genotypes would predominate in drug-free refuges and help keep resistant ones from taking over the population. Drug sanctuaries could be used in hospitals, for example, if different wards restrict the use of different drugs (generating a form of spatial sanctuary) or by alternating the use of a drug on the same ward over time (a form of temporal sanctuary).

But which of these forms of sanctuary, space or time, is more effective at slowing the spread of resistance? It turns out that models for how genes under selection move through populations when the environment varies in time and space can guide us here (see Levene 1953, Dempster 1955, Felsenstein 1976). Variation in time is like paying taxes: you can’t avoid it. The type that evolves in a temporally varying environment is the one that does best across all conditions experienced. Spatial variation, on the other hand, provides more options because the different patches can act as refuges for specialized types that do well on that patch. Because those patches are always available, then specialists can coexist indefinitely. At least in theory.

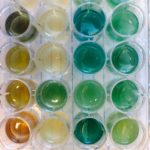

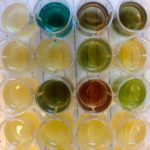

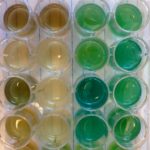

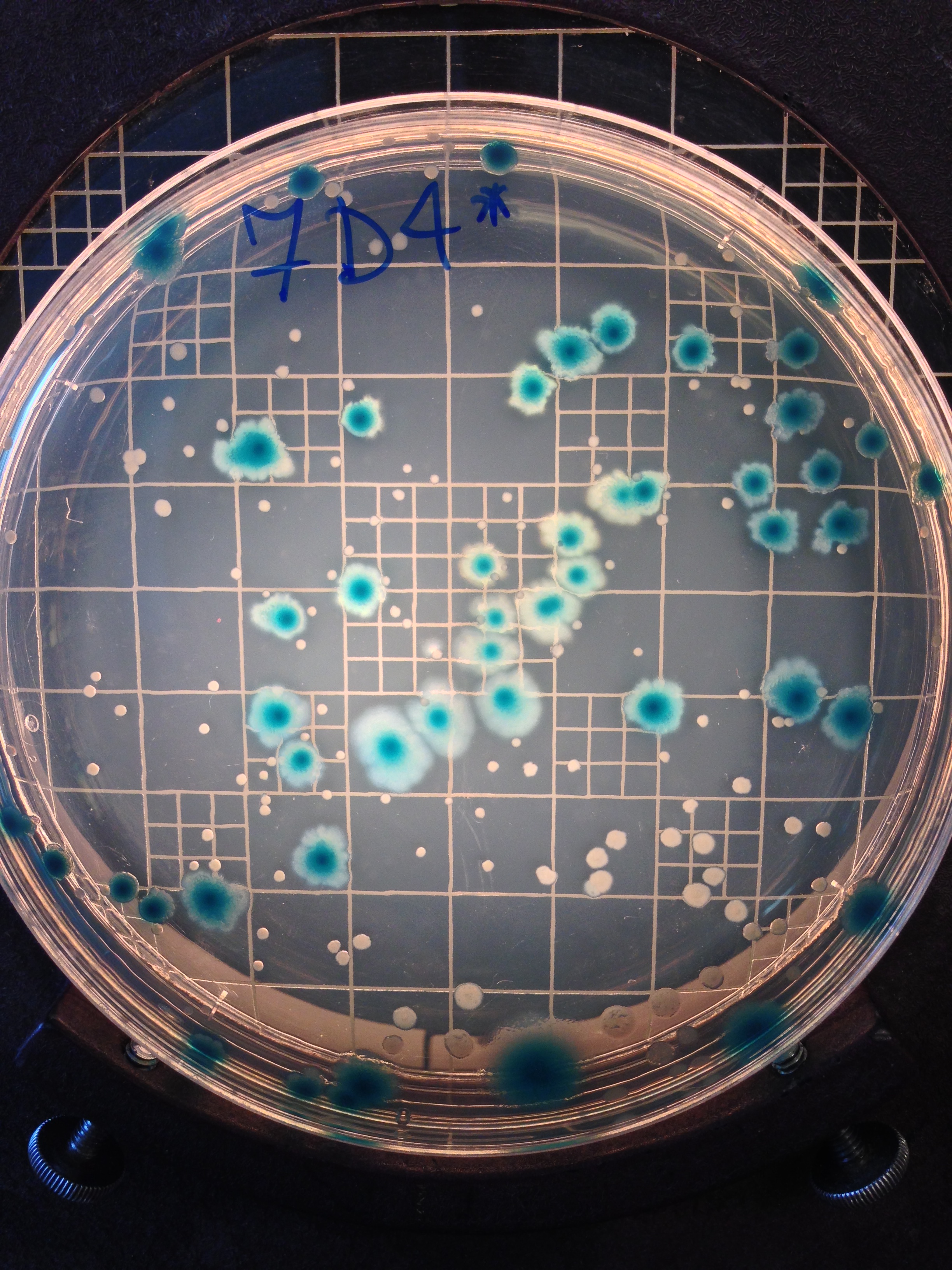

What does the data say? Our recent work in Evolution Letters, which involved allowing populations of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa to evolve in the presence or absence of the commonly used antibiotic, ciprofloxacin, and tracking the emergence and fate of resistant genotypes along the way, was very clear: drug sanctuaries in space, but not time, can slow the spread of resistance, just as the theory predicts. In space, resistant and sensitive genotypes coexisted because of a trade-off between resistance and growth in the absence of antibiotic: resistant types could not grow as well as sensitive types in the absence of drug, and the reverse was the case when the drug was present. In time, a single, generalist genotype evolved that was both resistant and grew well in the absence of drug. These results are exactly what is expected from theory and they tell us that drug sanctuaries in space could be effective at managing drug resistance.

Above: Pseudomonas aeruginosa cultures in Luria-Bertrani media during our selection experiment. Photo: Alanna Leale

But we also noticed something else that was not expected. Over time, the trade-offs that ensured coexistence between resistant and sensitive types broke down. In fact, the resistant strains started to gain mutations that improved their ability to grow in the absence of drug. The result was that, by the end of the experiment, most populations in the spatial sanctuary were dominated by resistant strains. The take home message here is that drug sanctuaries in space may be effective at slowing the rate at which resistant genotypes spread, they cannot prevent resistant strains from taking over the entire population eventually.

The prognosis for using drug sanctuaries as a form of evolutionary management of resistance is therefore mixed. Drug sanctuaries in space do help: while they cannot prevent resistance from evolving in the first place, they can slow the rate at which it spreads through a population, at least relative to drug sanctuaries in time. In the long run, however, when selection has had more time to do its work, the trade-offs that prevent resistant strains from taking over can be broken down by mutation and lead to the evolution of a generalist type that is both resistant and grows well in the absence of drug.

Of course, our experiments are highly contrived and restricted to one strain of one pathogen evolving in response to one drug in the defined and controlled conditions of a laboratory. Whether our conclusions hold for other bugs and other drugs, or more complicated networks of transmission characteristic of hospitals and the communities they are embedded in, remains to be seen. What our work allows us to do is get directly at the ecological and genetic mechanisms responsible for the emergence, coexistence, and eventual demise of diversity. Using these evolutionary principles in more complex, real-world situations to manage our existing arsenal of drugs for as long as possible, will be a major challenge for evolutionary biology in the years to come.

The full study, by Alanna Leale & Rees Kassen, is freely available to read and download from Evolution Letters.