Imagine a cheetah hunting without eyes or a blind squirrel trying to jump between tree branches – from top predators to small rodents, most mammals rely on vision to survive. Despite this shared reliance on vision, mammals show high variation in some vision-related traits and visual abilities across species. Different species also need to see in very different environments. Some need to watch out for predators in an open field, while others use depth perception to navigate dense forests.

Eyes are complex, and many eye-related traits need to work together for proper vision to occur. Some of these traits, and their differences across mammals, are easy to observe, such as the side-facing eyes of a rabbit or the rectangular pupils of a goat. But other eye traits are, ironically, harder to see. For example, the retina is a tissue in the back of the eye that receives the visual image. Some cells in the retina absorb light and transfer this signal to other retinal cells, which then send the signal to the brain. The arrangements of these cells within the retina can be quite different across mammal species. The cell structure of the retina could interact with traits such as eye position to alter how an animal sees. Do functional relationships among eye traits affect how they evolve in response to different visual environments?

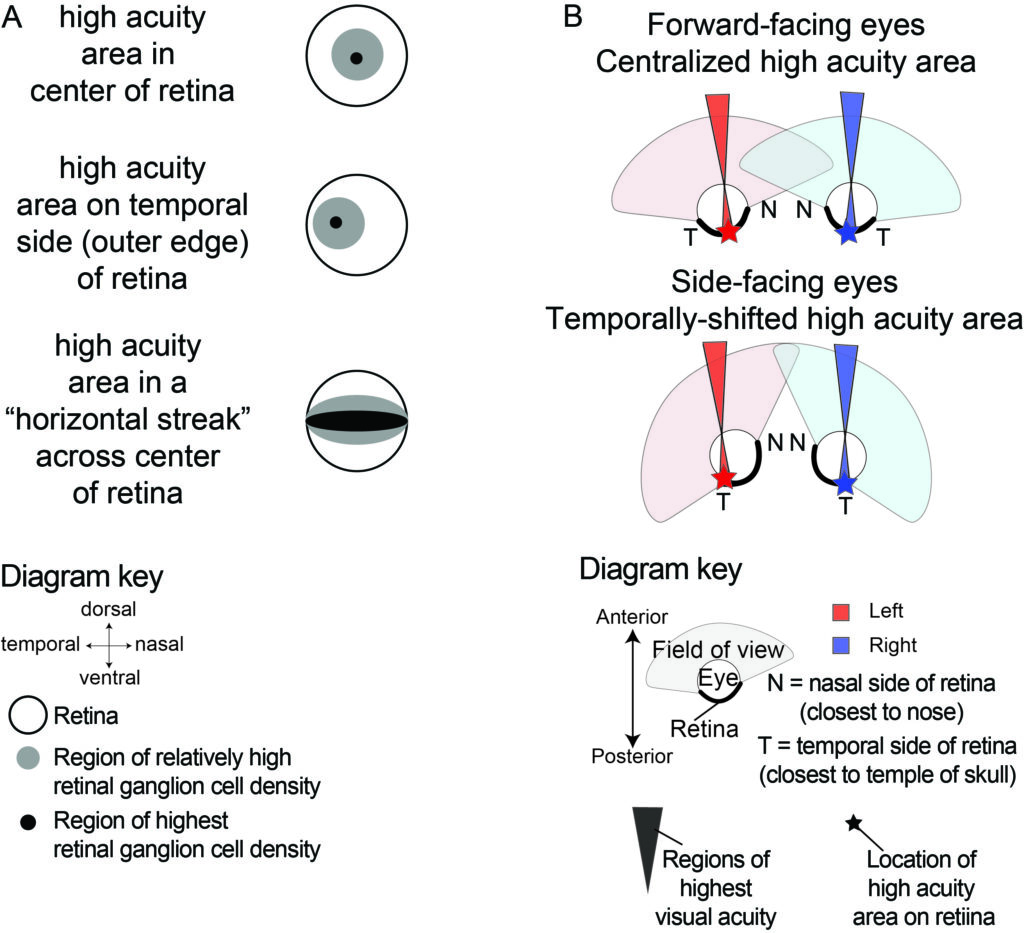

The cells that send the visual signal to the brain are called retinal ganglion cells, and they are thought to be important for visual acuity, or how clearly we see. If you look at a chart with letters in an eye doctor’s office, the smaller the letters you can see clearly, the higher your visual acuity is. Different animals have very different ganglion cell densities, suggesting some see much more clearly than others. Furthermore, the density of ganglion cells is not even across the retina. The human retina, for example, ranges over 100-fold from 200 cells/mm2 near the outer edge to 38,000 cells/mm2 towards the center. Many mammals have a “high acuity area” like humans, where the retinal ganglion cells are very dense. But the shape and position of this high acuity area is highly variable across species. Some animals have a centralized high acuity area, like humans. Others have this high acuity area shifted to one side of the retina. Some also have high density in a horizontal streak pattern across the horizontal plane of the retina (Figure 1A).

Why do mammals have these different patterns of retinal high acuity areas? One hypothesis is that they correspond with a species’ visual environment. For example, the horizontal streak may be beneficial for animals living in horizon-dominated habitats, where they mostly need to see in the horizontal plane. This includes species that forage on the ground, instead of being up in trees, underwater, or flying through the air. We tested this hypothesis by asking if ground foraging species were more likely to have a horizontal streak. We found that ground-foraging species were significantly more likely to have a horizontal streak compared to species that forage in other areas such as in trees, underwater, or in the air. However, closely related species may share traits because the trait arose in a common ancestor and was passed down to all descendent species. We used a method that takes into account information from a phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary relationships among species and found that the horizontal streak was associated with ground foraging even after controlling for shared evolutionary history.

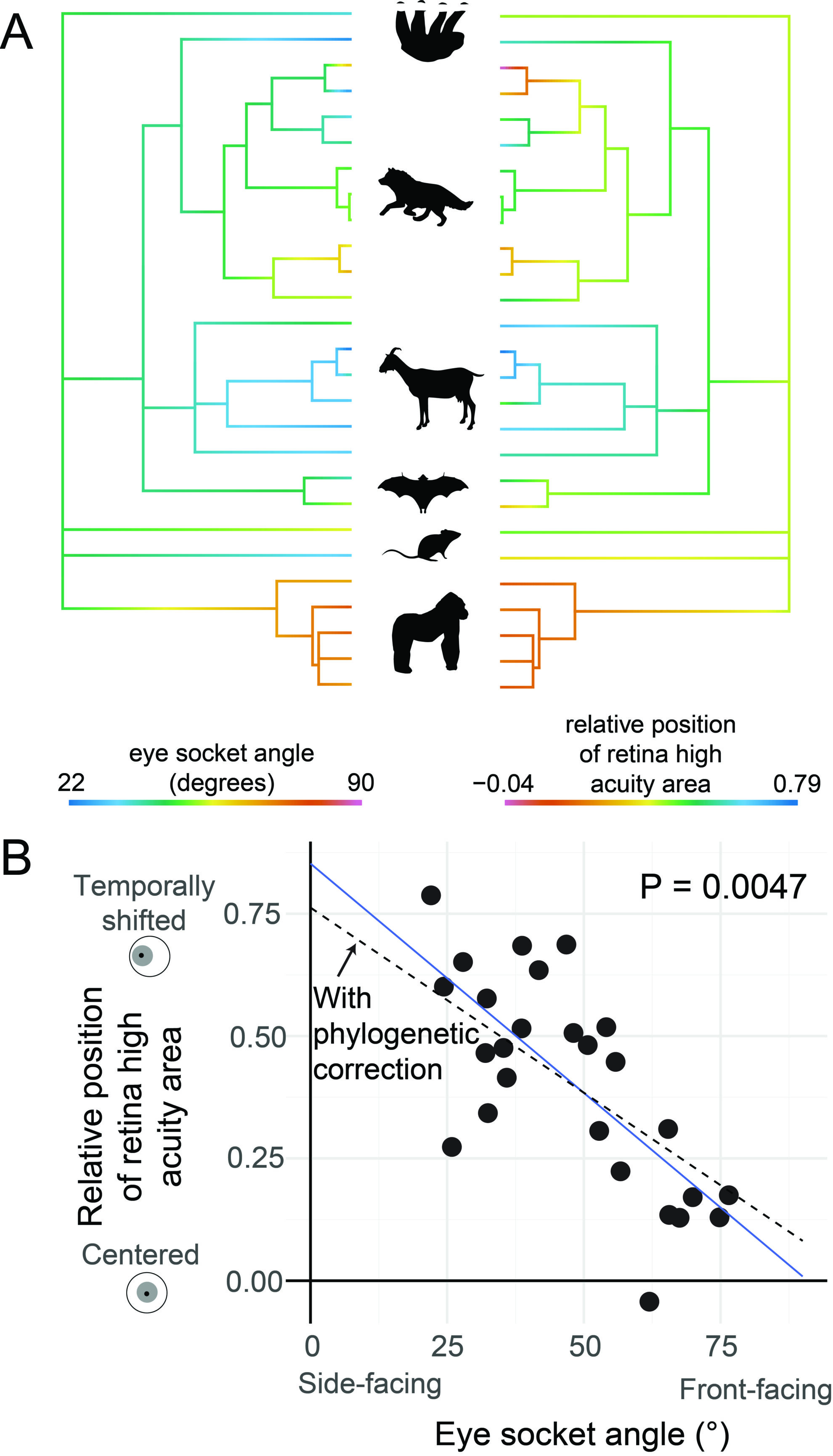

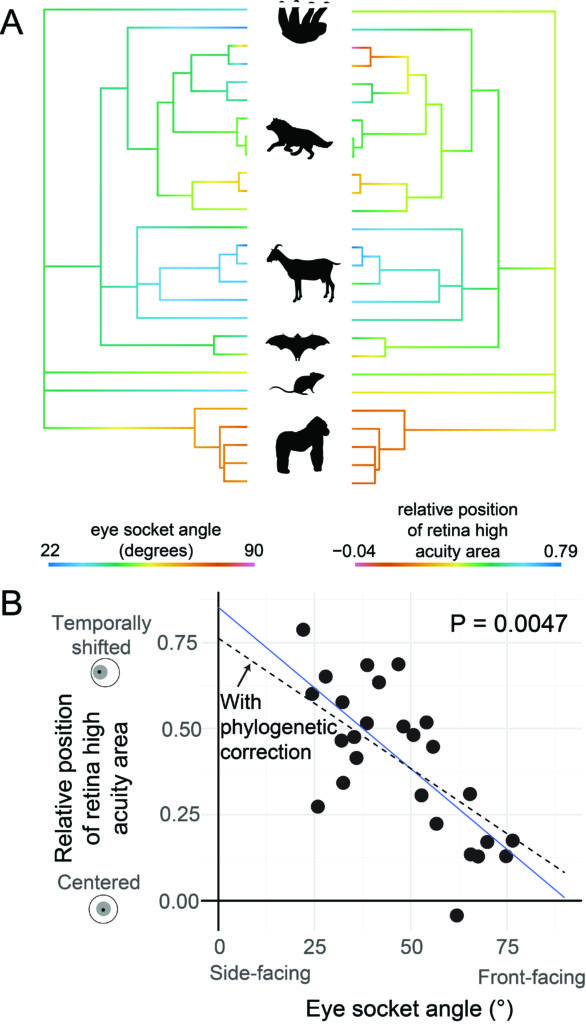

Another hypothesis for the diversity of retina high acuity areas is that their position may evolve to compensate for orbit convergence, or the angle of the eyes in the head. Many mammals like humans, cats, or bears have eyes that face more towards the front, whereas other mammals like deer or rabbits have eyes that face sideways. There is a popular idea that “predator” species have forward-facing eyes, while “prey” species have side-facing eyes, but our work showed that these relationships may be more complicated than once thought. In addition to the angle of the eyes in the head, the position of the high acuity area may also have an important effect on the direction in which an animal sees. Previous studies observed that animals with side-facing eyes tend to have the high acuity area shifted towards the “temporal” side of the retina, closer to the temple of the skull (i.e., the outer edge of the retina). Because of the way the eye is curved, this would mean the high acuity area points forwards in an animal with side-facing eyes (Figure 1B). We set out to test this hypothesis using several species representing many of the major groups within mammals and accounting for shared evolutionary history, like in our previous analysis. To do this, we measured orbit, or eye socket, angles using museum specimen skulls from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Figure 2).

We found a strong negative correlation between eye angle and the position of the high acuity area in the retina. In other words, species with more side-facing eyes have high acuity areas shifted more towards the outer edge of the retina, supporting our hypothesis. Following the trend of our data, an animal with completely side-facing eyes (0° angle) would be predicted to have a high acuity area shifted almost entirely to the outer edge of the retina, while an animal with completely forward-facing eyes (90° angle) would be predicted to have a central high acuity area with almost no shift to either side of the retina. This means that the high acuity area is predicted to face directly forwards in mammals, regardless of the angle of the eyes. This is also consistent with behavioral observations – if you startle a deer in the forest, it will look at you head-on despite having side-facing eyes, so it may see best in the forward direction.

Our work shows the importance of considering both the environment and functional relationships between traits to understand the evolution of the eye. Many sensory systems involve complex interactions between different types of traits, and understanding relationships among these traits may help us better understand how sensory systems evolve in response to the environment.