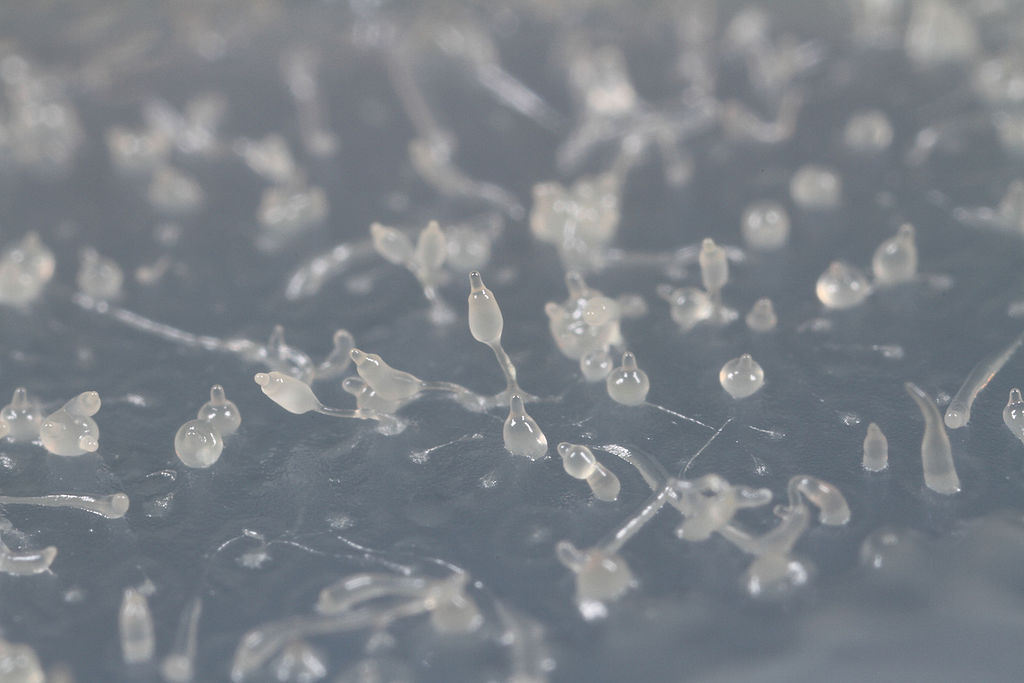

Dicty (Dictyostelium discoideum) are an interesting organism that has both a single-cell and multicellular stage in its life cycle. Dicty amoebas in the wild typically dwell in forest soils and feed on bacteria. They also are associated with three species of symbiotic bacteria (symbionts) in the genus Paraburkholderia that have evidently figured out how to survive and thrive within their amoeba hosts.

The work for this paper came about from a seemingly simple question: why is it that all Dicty can carry Paraburkholderia symbionts in the lab, but not all field-collected Dicty possess a Paraburkholderia symbiont?

From previous work, we knew that two of the Paraburkholderia symbionts had reduced genome sizes relative to a third symbiont and other Paraburkholderia species. Coevolving hosts and symbionts tend to influence each other in a semi-predictable way, so the difference in genome sizes indicated to us that pairings of Dicty with one of these reduced genome symbionts means a potentially longer evolutionary history of association between the two organisms.

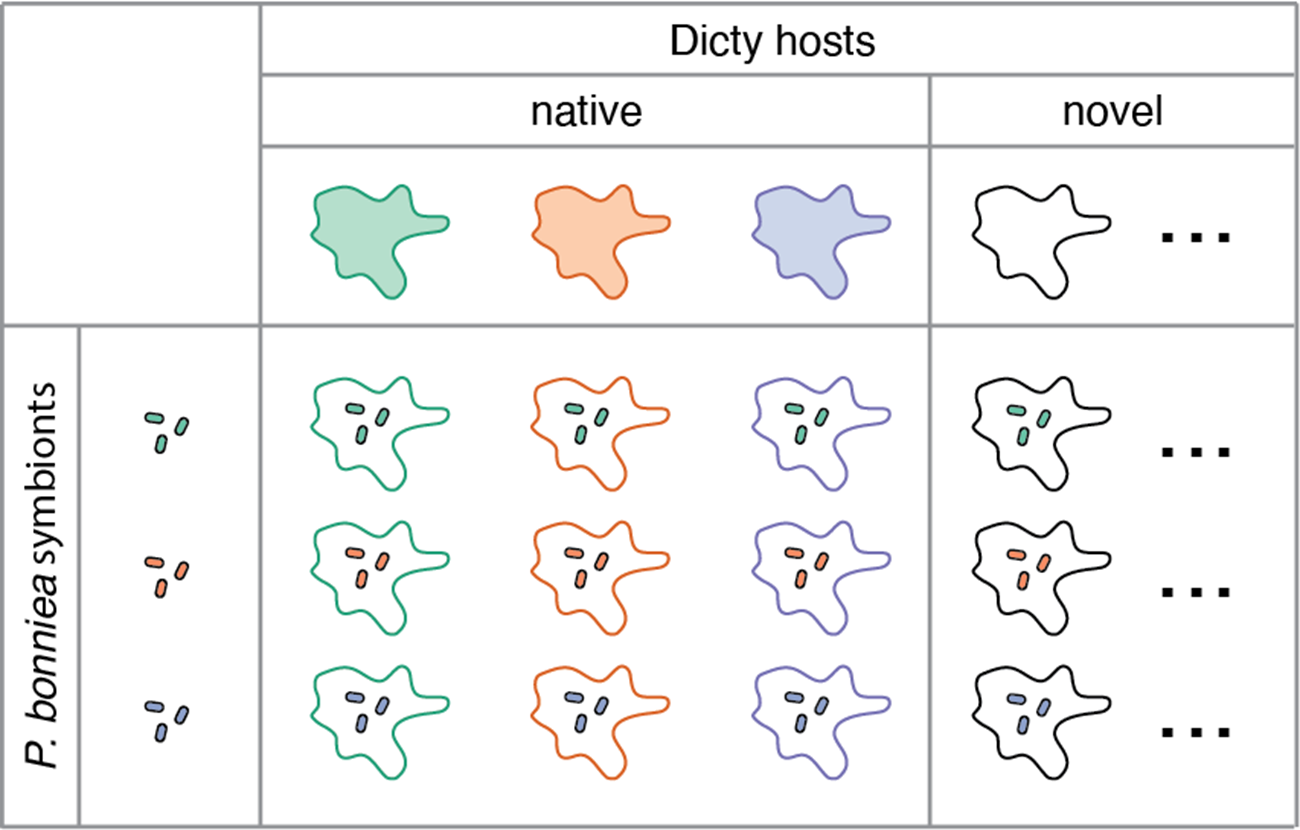

We used one of these reduced genome species, P. bonniea, in our experiments to test whether the answer to our original question might lie in naturally co-occurring pairings of host and symbiont strains being mutually adapted to being together through coevolution. In other words, maybe the field-collected Dicty that come with their own P. bonniea are the ones that have higher fitness than other potential hosts when together with this symbiont. Similarly, maybe the field-collected P. bonniea from those Dicty hosts are the ones that have higher fitness when associated with those hosts compared to other potential symbionts.

We combined Dicty and P. bonniea in various native (naturally co-occurring) vs. novel pairings to tease apart whether intrinsic differences due to ongoing coevolution among strains of hosts and symbionts contribute to the variable fitness consequences of association. It turns out native hosts to P. bonniea are not more fit than novel hosts under this circumstance. P. bonniea symbionts also did equally well regardless of host type. What we found instead is that one of the P. bonniea strains didn’t harm their Dicty hosts as much as other strains. This benevolent strain was also better at transmitting from one host to another.

These experiments involved some clever experimental design that we are proud of, and a lot of dedicated undergraduate student coauthors. We have thoughts about what these results mean in the Discussion section of the paper. We hope you will give it a read!