In our latest author blog, Gonçalo Faria explains how his new paper in Evolution Letters investigates the connections between two classic ideas in evolutionary biology: the “sexy son hypothesis” and the “greenbeard effect”.

Two major theories dominate contemporary evolutionary biology: sexual selection, which concerns how natural selection can work through differences in mating success; and kin selection, which concerns how natural selection can work through the reproductive success of an individual’s genetic relatives. Both theories made their first appearance in Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, and have subsequently developed into enormous literatures – with surprisingly little cross-talk between them.

Darwin went onto greatly develop the theory of sexual selection in his massive tome The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. An early champion of this theory was R. A. Fisher, who suggested what is now known as the “sexy son hypothesis”. According to this idea, females will be favoured to preferentially mate with males who exhibit conspicuous ornamentation if other females already happen to find this ornamentation attractive because, by mating with ornamented males, females will be more likely to have ornamented sons, who will be more attractive to potential mating partners.

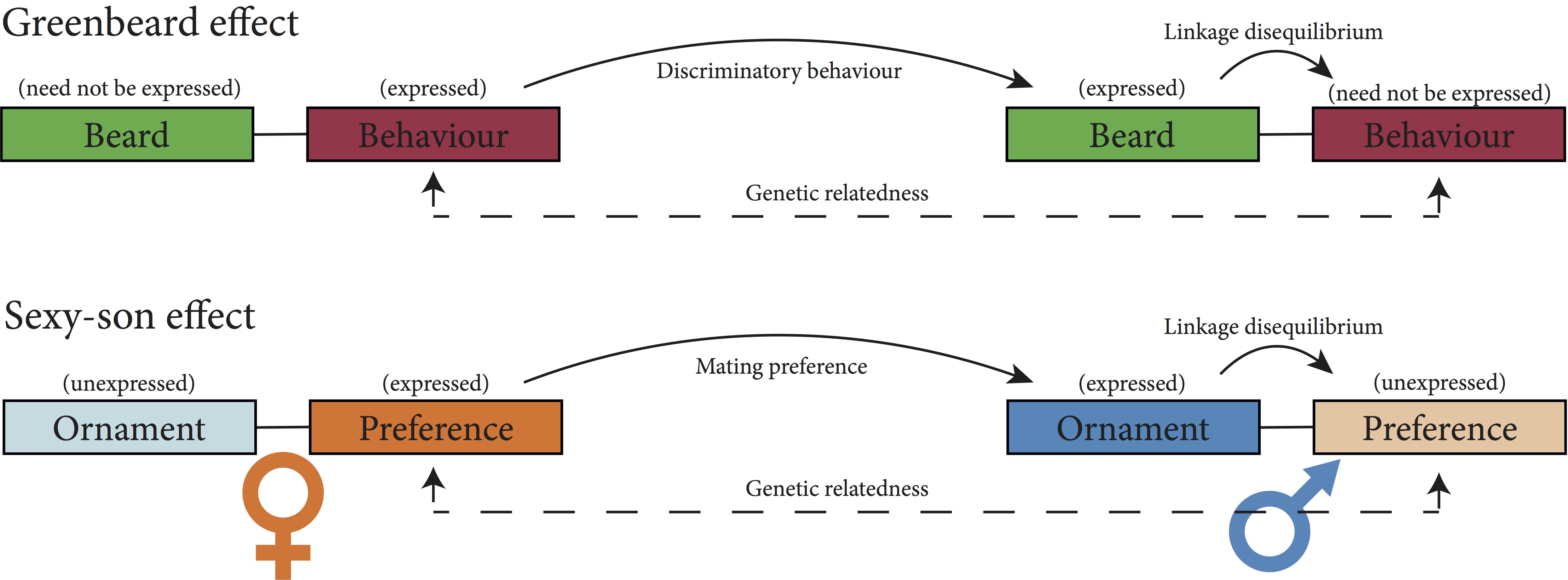

Building upon Darwin’s initial musings that kin selection could explain the adaptations of sterile workers in insect societies, Hamilton developed these ideas into a general mathematical theory of how natural selection works both through the individual’s own reproduction and that of its relatives. In doing so, he proposed what is now known by the “greenbeard effect” – this colourful name being coined by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene – to explain how altruistic behaviours could evolve in absence of genealogical relatedness. The idea assents on two genes being present. One of the genes causes a display of a conspicuous marker, such as a green beard. The other gene cause its carriers to act altruistically toward individuals carrying a green beard. If the two genes tend to be associated within the same individuals, then the altruistic behaviour can be favoured by natural selection because it is ultimately helping copies of itself.

My paper, co-authored with my PhD supervisors, Susana Varela and Andy Gardner, concerns the idea that the sexy-son effect is a kind of greenbeard effect. Specifically, if females vary in their preference, and males in their ornamentation, then the resulting assortative mating of choosy females with ornamented males ensures that the alleles underpinning female preference and male ornamentation will tend to be present in the same individuals. Therefore, when a female carrier of the preference allele mates with an ornamented male, she is likely providing a fitness benefit to a carrier of the same allele. This appear to be equivalent to the greenbeard effect, where carriers of the altruistic allele provide a fitness benefit to green bearded individuals, likely carrying the same altruistic allele. This possibility had been discussed by Dawkins in The Blind Watchmaker and later by Gardner, in a paper co-authored with Tommaso Pizzari, but had not been explored formally. If this is correct, then it should be possible to integrate the concepts and approaches of those two different effects and that is the objective of our work. We do this in four different parts.

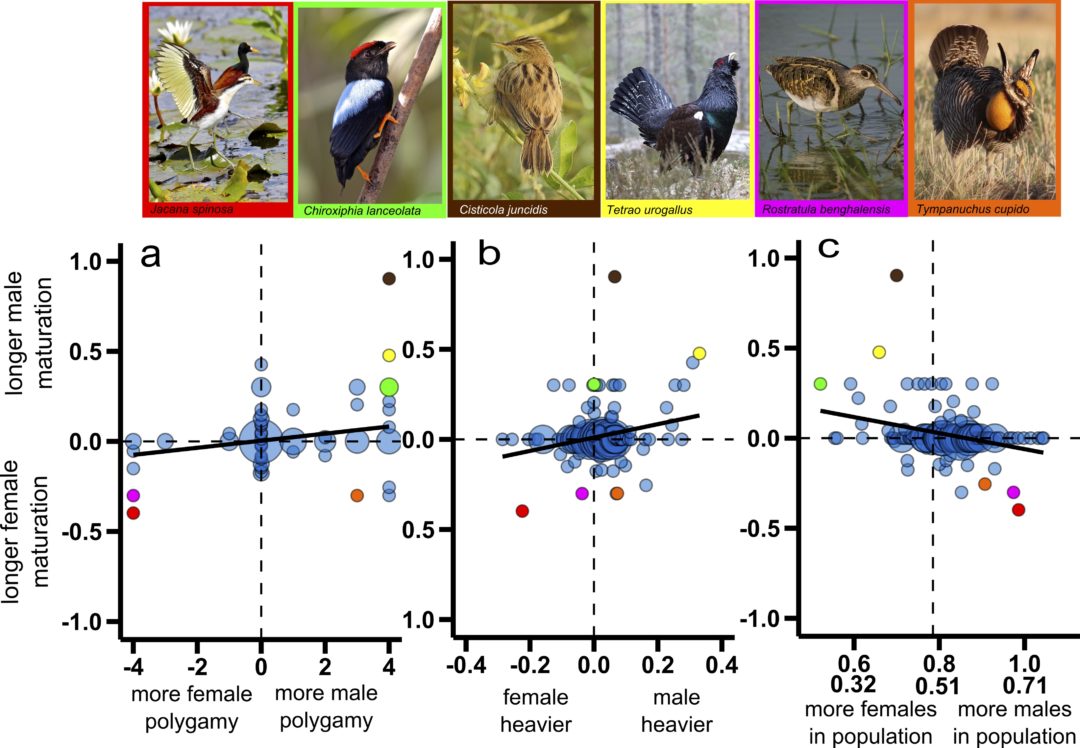

First, we ask what kind of greenbeard effect is involved in the sexy-son effect. In the greenbeard effect literature, four broad categories can be used to classify greenbeard effects: facultative-helping greenbeards, where greenbeards enact helping behaviour toward fellow greenbeards but not toward non-greenbeards; facultative-harming greenbeards, where individuals enact harming behaviour towards non-greenbeards but not towards fellow greenbeards; obligate-helping greenbeards enact helping behaviour toward all social partners, but only fellow greenbeards are able to benefit from this; and obligate-harming greenbeards enact harming behaviour toward all social partners, but only non-greenbeards are vulnerable to its deleterious effects. It turns out that those same categories can be used to distinguish four different types of sexy-son effects, depending on how female preference is being enacted and its effect upon ornamented and non-ornamented males.

Second, we investigate if the sexy-son effect is also vulnerable to what is known, in the greenbeard literature, as the problem of “falsebeards”. Falsebeards are those individuals who cheat by growing a beard but without enacting any altruism. Pizzari and Gardner suggested that the sexy-son effect may involve a kind of greenbeard effect that is relatively resistant to falsebeards. Specifically, the presence of assortative mating may continually build up the association between the two traits, preventing the breakdown of the effect through the evolution of falsebeards. Incorporating assortative mating into a greenbeard effect model, however, does not prevent the problem of falsebeards and, in fact, the sexy-son effect suffers from an equivalent problem, known in the literature as the lek paradox, whereby female preference makes itself redundant by eliminating the very genetic variation that defines preferred versus non-preferred males.

Might, then, the solution that have been identified for the lek paradox have application in the problem of falsebeards? This is the third question of our work. One well-known way to prevent the lek paradox is to continually fuel variation into the male ornament locus, such that female preference does not become redundant. We find that simply introducing mutants does not help, but it does stabilize the greenbeard effect if assortative mating is also present. This highlights the similarities between the problem of falsebeards and the lek paradox and, consequently, the similarity between the greenbeard effect and the sexy-son effect.

Lastly, both greenbeard and sexy-son effects have difficulties to get off the ground. Specifically, they both require a high frequency of discriminatory behaviour to be already present in the population before the effects themselves start being favoured by natural selection. Gardner, in an article written with Stuart West, showed that population structure can help the establishment of the greenbeard effect in the population because local social interactions allow the frequency of greenbeard individuals to be locally high enough to be favoured, even if they are globally rare. Our final contribution is to show that population structure is also a possible solution to help sexy-son effects to evolve from rarity.

This works illustrates how, if a conceptual bridge can be built between two different topics, old results can lead to new insights in unexpected places.

Gonçalo Faria is a PhD student at the School of Biology, University of St. Andrews. The full paper is freely available to read and download from Evolution letters here.